My last post described the first two of five new (as of yesterday) publications on PSP to suddenly appear on my routine PubMed search. The third one is sufficiently interesting and complicated to deserve its own post.

—-

Falls are perhaps the earliest-appearing and most disabling feature of PSP, but we don’t yet fully understand which of the many brain areas involved in PSP deserves most of the blame.

A PSP-like illness endemic to the islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique is called Guadeloupean tauopathy or Caribbean Parkinsonism (CAP). It may be the result of consuming two fruits, sweetsop and soursop, which have high levels of a mitochondrial toxin called annonacin. Injected into rats in a lab, annonacin produces a PSP-like illness complete with abnormal tau accumulation. However, the human CAP illness includes multiple aggregating proteins in addition to tau.

The new article from neurologists in Paris and on Guadeloupe and Martinique reports on careful measurements of atrophy of specific brain regions on MRI in 16 patients with CAP, 15 with PSP-Richardson syndrome and 17 healthy, age-matched control participants. They correlated the results with 11 standard scales assessing gait, general movement and cognitive function and also with electronic measures of gait and eye movement. The group’s senior leader was Dr. Annie Lannuzel of INSERM, France’s equivalent of the NIH. She has a long record of research in CAP. The first author was Dr. Marie-Laure Welter, also of INSERM.

The results were that PSP and CAP differed in their anatomical patterns of brain atrophy. Although their overall average disease severity was similar, CAP had more cognitive loss with correspondingly more atrophy of cerebral cortex. On the other hand, the PSP group had more gait instability with correspondingly greater involvement of the midbrain and cerebellum.

The overall statistical comparisons showed that the main source of the gait and balance problem in PSP is damage to the supplementary motor area – pedunculopontine nucleus (SMA-PPN) network. In CAP the gait/balance problem includes the SMA-PPN but with a major contribution from areas serving general attention and self-awareness.

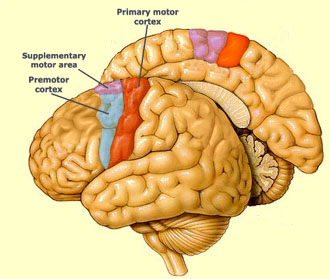

The SMA is an area of frontal cortex just in front of the primary motor cortex.

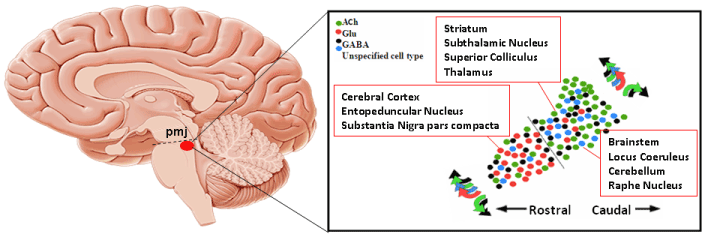

The PPN is a complex nucleus at the pons-midbrain junction (PMJ, below):

Here’s why this paper’s results could be important:

The SMA, as you can see from its superficial location, is an easy target for non-invasive magnetic or electrical trans-cranial stimulation. TCS is still in its infancy but is starting to show some modest benefits for some movement and cognitive disorders.

The PPN has long been known to be important to the balance issue in PSP and Parkinson’s. This new research result focuses attention on that nucleus as a potential target for deep-brain stimulation or as a target for surgically implantable stem cells or viral vehicles of genes for depleted enzymes. Dr. Stuart Clark and colleagues at The State University of New York, Buffalo have already created an experimental model of PSP in rats by altering the function of the PPN. The results from Welter et al tend to validate the relevance of that model to PSP.