Yesterday’s post was about how the 10 most-frequently-visited news items in Parkinson’s News Today (PNT) of 2025 might relate to PSP. The list appeared here.

I covered items #10 to #6 in my last post.

And now: #5 to #1 .

#5: FDA clears early trial of stem cell therapy for Parkinson’s

The treatment, called XS-411, is made from stem cells derived from multiple healthy donors and converted into dopamine-producing cells. Each patient would receive one injection of such cells into each side of the putamen, the brain area where the dopamine synapses are located. The FDA approved a Phase I trial in April 2025, but now, nine months later, clinicaltrials.gov lists two small studies in China but none in the US. Most current stem cell trials in neurology derive the cells from the patient’s own bone marrow or skin biopsy, so I really don’t know why the company, XellSmart Bop-Pharmaceutical Company of Suzhow, China, is using cells from people other than the patients themselves. Maybe they have a new way to suppress the immunologic rejection or maybe production using multiple donors is more easily scalable to serve large numbers of patients. Could XS-411 work in PSP? Perhaps it could help the same fraction who respond to levodopa, which is only a minority, and their benefit is usually modest and transient. The problem is that in PSP, unlike in PD, the cells in the putamen receiving the dopamine-encoded signals are degenerating along with the dopamine-producing cells. So, we need more research into injecting stem cells producing neuroprotective molecules or non-dopamine neurotransmitters.

#4: Program offers psychedelics as treatment for Parkinson’s

Ibogaine is a psychedelic drug legal only in a few states, and even then only for FDA-approved research use. Ambio is a company offering the drug to people with a wide variety of conditions on a “research” basis at clinics in Mexico and Malta. There’s no such listing in clinicaltrials.gov, so I can’t be sure of the protocol except that patients are charged $6,050 for a four-day treatment initiation at one of their clinics and “micro-doses” for the next six months. Based on the little information available, this fits the profile of many “research trials” of alternative treatments: a hefty fee, minimal pre-treatment evaluation or followup, no control group and no peer-reviewed publication. In this case, I must also wonder about the risk of habituation to the treatment itself, and where do you suppose you could buy something to satisfy that? Enough – you now know what I think about this drug for PSP, even if the initial $6,050 and the travel expenses are not an issue for you. To be sure, some alternative treatments do have legitimate potential, but when there’s a major risk of financial or medical harm (both of which apply here), their use should be confined to formal FDA-approved research protocols.

#3: Bacteria in digestive tract tied to cognitive decline

Parkinson’s disease is a natural candidate for causation by intestinal bacteria because the first stage of the disease, aggregates of the alpha-synuclein protein in neurons, starts not in the brain, but in the intestines and lungs. But PSP does appear to start in the brain. There’s been little research on gut bacteria and PSP, but something important was reported in 2023 from researchers in China and summarized in my 4/2/23 post. That short-term study found that replacing the colonic bacteria produced about a 10 percent benefit in the PSP Rating Scale score. The trial was too short and small to conclude anything about long-term slowing of progression. Bottom line: Although PSP does not start in the GI tract as PD does, gut bacteria may play a role and should be studied further for any therapeutic implications.

#2: Study identifies potential way to treat Parkinson’s constipation

Ghrelin is a string of 28 amino acids with many basic gastrointestinal functions including stimulating appetite at the level of the brain and defecation at the level of the spinal cord. The article reported by PNT teased out an important detail that could hold implications for treatment of constipation in those with PD. We don’t know if applies as well to the constipation of PSP, but I can say that some of PSP’s constipation is caused by degeneration of a cluster of cells in the lower spinal cord that are not involved in PD. One research study, from 2013, did find a role of ghrelin in multiple system atrophy but not in PSP or corticobasal syndrome. So, those few strands of evidence suggest that people with PSP will have to rely on traditional methods of keeping things moving – exercise, fluids, fiber, a stool softener, and avoidance of drugs that block acetylcholine synapses (“anticholinergics”). Many drugs in the last category are used for other PSP symptoms such as imbalance, vertigo, urinary incontinence and depression, so getting off those is a good topic for discussion at the neurologist’s office.

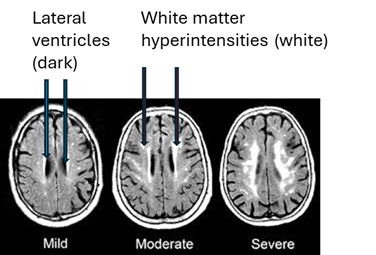

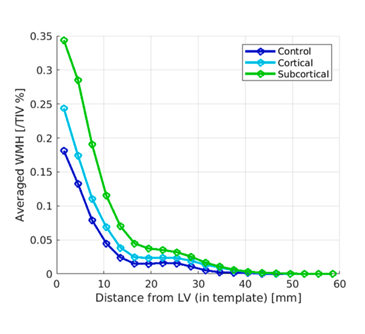

#1: Research shows disrupted mitochondrial DNA tied to inflammation

For decades, we’ve known that in both PD and PSP, the cells’ mitochondria malfunction and there’s excessive inflammation in the brain. But we don’t know which is cause and which is effect, or if they’re both effects of a common cause. The new study used a novel genetic technique to find evidence that it’s the inflammation causing the mitochondrial loss. In theory, the same study could be performed in PSP. A similar result would suggest that to slow PSP progression, targeting excessive inflammation might do better than those targeting mitochondria directly. Early in my career, I had narrowed my subspecialty choices down to movement disorders and neuroimmunology/multiple sclerosis. I chose the former because I was flummoxed by the complexity of the immune system. Little did I know . . .