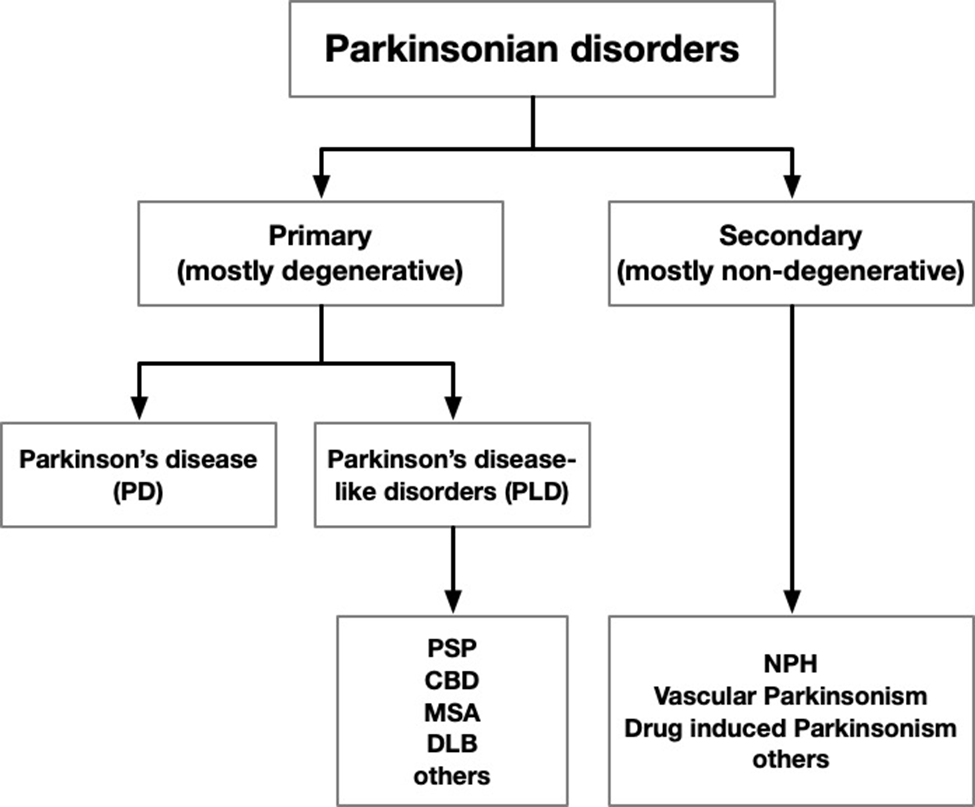

One of this blog’s frequent commenters — OK, it’s my pal Jack Phillips, CurePSP’s Board Chair — prompted by my 3/8 26 post, has asked which of the three PSP Trial Platform drugs to bet on. That’s a tough one, partly because unlike racehorses, each has a different mechanism of action, so it’s an apples/oranges/peaches comparison. But as long as I don’t have to worry about peer review of my blog posts, here’s what I’m thinking at this point:

- The AADvac anti-tau vaccine induces one’s immune system to make anti-tau antibodies, so one might expect it to do no better than the two failed passive (i.e., directly infused) monoclonal antibodies from a few years ago. But the antibodies formed in response to AADvac recognize the middle part of the tau protein, while the monoclonals recognized the initial (i.e., N-terminal) end. There’s good evidence now that the toxic part of abnormal tau is in AADvac’s middle-domain wheelhouse. So, the questions now are:

- Has tau already done its dirty work before reaching the form or location susceptible to the antibody?

- Most of the damage done by tau happens inside the brain cells, where antibodies can’t reach. The hope is to pick off the abnormal tau in transition from one brain cell to another. That works in mice with an abnormal version of the tau gene that causes a familial form of frontotemporal dementia with Parkinsonism. But FTDP isn’t quite PSP and mice aren’t quite people.

- LM11A-31 is very different. It enhances the brain’s ability to repair existing damage. It has shown benefit in a number of different animals models of different diseases with different aggregating proteins (or with none). In humans with neurodegenerative diseases, the only published experience is in Alzheimer’s disease, where the benefit was modest, though the study was too small to assess efficacy in a valid way. My concerns are that:

- The drug’s modulation of the cells’ compensatory mechanisms might be too subtle to stand up to the onslaught of misfolded tau and other perturbations present in PSP.

- Starting from an early stage of involvement in PSP, brain cells transmit misfolded tau to other cells. It’s possible that this happens before the cells have lost much of their functional abilities, perhaps before the mechanisms that LM11A-31 modulates become relevant.

- AZP-2006 improves lysosomal function, thereby helping the cells dispose of tau that’s overabundant, misfolded, aggregated or excessively phosphorylated. I personally favor that idea for three main reasons:

- The high frequency of co-pathology (where the tauopathies have mild levels of other aggregating proteins) suggests that specific defects in a shared garbage disposal system affect specific combinations of proteins. This in turn implies that if the predominantly affected protein is tau, then a tauopathy develops, with a few aggregates of other proteins such as α-synuclein, TDP-43 and others. I’d done research on the PSP cluster in a group of towns in northern France with severe ground contamination by multiple industrial metals. Lab experiments (performed in collaboration with a team under Drs. Aimee Kao and Carolina Alquezar at UCSF) have suggested that some of the metals in that environment can damage the disposal mechanism without affecting the production of tau itself. That suggests that a treatment like AZP-2006 aimed at that mechanism could work.

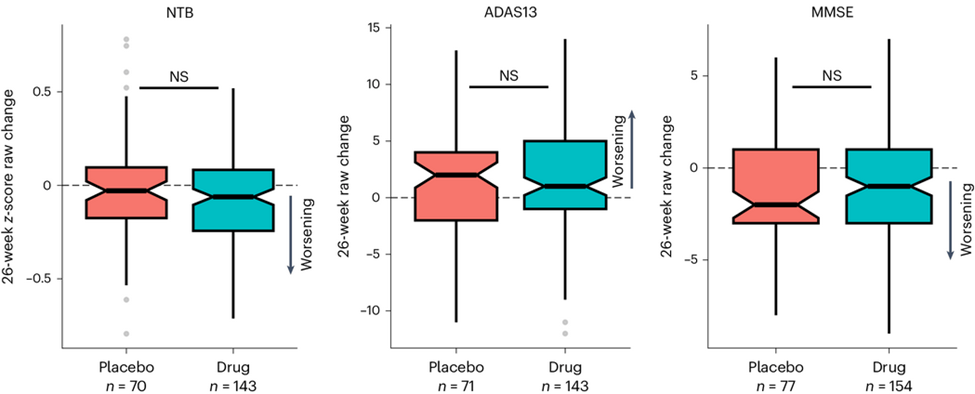

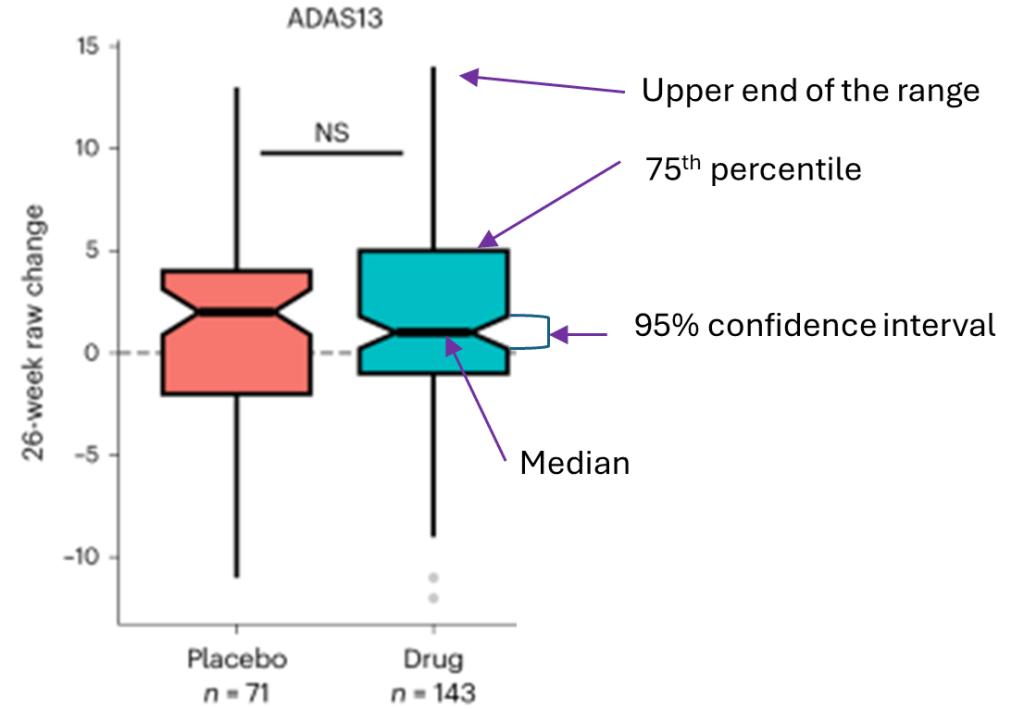

- AZP-2006 has already shown evidence of an ability to slow the progression of PSP. That trial, designed to detect safety and not efficacy, included only 24 patients on the active drug and lasted for only six months. So, the slowing of progression relative to placebo did not reach statistical significance. But its magnitude was most impressive. https://movementdisorders.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/mds.70049

So, my analysis gives AZP-2006 a slight edge among these three. But that’s based partly on results of my own research, so I have a sentimental bias. Then there are other drugs in the pipeline, like:

- NIO-752 (a tau-directed anti-sense oligonucleotide to reduce tau production)

- FNP-223 (an inhibitor of an enzyme that allows phosphate group to attach to tau)

- GV-1001 (mostly an anti-inflammatory to quell one important step in the disease process)

- Bepranemab (passive, mid-domain antibody infusions)

Besides, much smarter people than I have been crashingly wrong in predicting clinical efficacy of drugs. But it’s a good mental exercise to think about it.