The drug duloxetine, marketed under the brand name Cymbalta, was originally developed for depression or anxiety but is now prescribed mostly for pain management. An article from neurologists in Russia and Malaysia now reports that three people with PSP who were receiving duloxetine for their mood issues experienced important, unexpected improvement in their speech.

The article’s first author is Dr. Oybek Turgunkhujaev of the Semeynaya Clinic in Moscow and its senior author is Dr. Shen-Yang Lin of Universiti Malaya in Kuala Lumpur. Unfortunately, the journal, Movement Disorders Clinical Practice, is not open-access and because it’s only a brief article, there is no abstract in PubMed for me to link to.

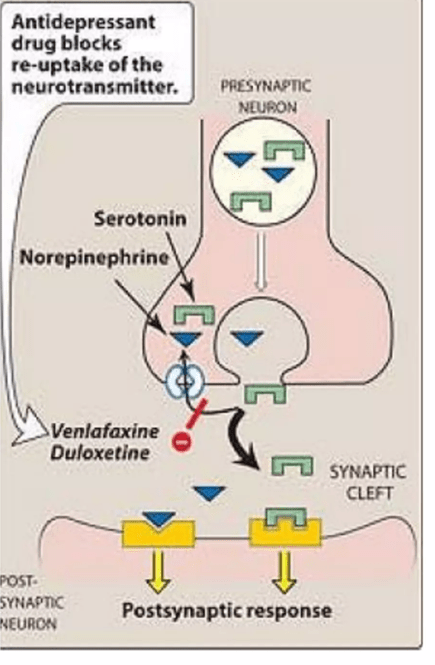

The mechanism of action duloxetine is to enhance the action of the neurotransmitters serotonin and norepinephrine by blocking the brain cell’s ability to re-absorb those molecules from the synapse. That’s a standard way for brain neurons to regulate and sharpen its signals to other neurons. That process is called “reuptake” and you’ve probably heard of the SSRIs or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Duloxetine works on norepinephrine as well as serotonin, so it’s an SNRI. Other SNRIs in common use include venlafaxine (Effexor) and desvenlafaxine (Pristiq). The figure below shows the mechanism of action of duloxetine and venlafaxine.

Nerd alert: This mostly takes place in the pons, specifically the locus ceruleus (for norepinephrine), raphe nuclei (for serotonin), but to a lesser extent in prefrontal cortex of the cerebrum (both norepinephrine and serotonin).

The journal article is accompanied by before-and-after videos of two of the three patients. They all had difficulties not only with slurring, but also with difficulties initiating speech and stuttering. The delay to onset of the drug’s benefit is described only as “within weeks.” All three patients also experienced an improvement in their mood, which could have been a direct effect of the drug on the natural reaction to their improved ability to speak.

The authors do a good job of describing how the drug’s known mechanism of action might address the parts of the brain that when impaired, are known to cause those symptoms. But they also recognize that the general alerting and energizing effect of duloxetine could explain the result as well. Placebo effect seems unlikely, as the durations of benefit were too long: “> 3 months,” “15 months until death” and “>5 months.”

Bottom line: This is encouraging and I hope further reports of duloxetine in PSP from other centers are forthcoming. BUT . . . and MEANWHILE . . .

Physicians considering prescribing duloxetine off-label for speech problems in PSP should be aware that it can have important side effects and drug/dietary interactions. I can’t get into those here, but they are described in detail in the 31-page FDA-approved package insert and its one-page summary. Needless to say, there has been no formal trial of duloxetine in PSP, so that population could have different/additional/worse side effects relative to the mostly younger people in the depression and pain trials on which the package insert was based.