You’ve all heard of the ten known PSP subtypes. They’re classified into three groups by the general areas of the brain involved (i.e., cortical vs. subcortical). Here’s the list:

- Cortical and subcortical (~50% of all PSP)

- PSP-Richardson syndrome (PSP-RS)

- Cortical (~20%)

- PSP-frontal (PSP-F)PSP-speech/language (PSP-SL)

- PSP-corticobasal syndrome (PSP-CBS)

- Subcortical (~30%)

- PSP-Parkinsonism (PSP-P)

- PSP-progressive gait freezing (PSP-PGF)

- PSP-postural instability (PSP-PI)

- PSP-ocular motor (PSP-OM)

- PSP-cerebellar (PSP-C)

- PSP-primary lateral sclerosis (PSP-PLS)

(As an aside: Neurodegenerative diseases are defined mostly by their pathological (i.e., microscopical) appearance, but each disease so defined may have several possible sets of outward signs and symptoms in the living person, depending on the general locations of the pathology within the brain. We deal with this by hyphenating the names of neurodegenerative diseases, with the pathology first and the clinical picture second.)

Now, to the news: Researchers at the Institute of Science in Tokyo, the Mayo Clinic, and UC San Diego have refined the above subtype classification. First author is Dr. Daisuke Ono, senior author Dr. Dennis Dickson and eight colleagues included 588 autopsy-proven cases of PSP from the Mayo brain bank without evidence of other neurodegenerative diseases. First, they used ChatGPT’s large-language software to extract clinical data from 53,527 pages of medical records, tabulating the order of appearance and progression rate of 12 pre-specified, PSP-related symptoms in each patient. Next, they performed a statistical technique standard for this sort of thing called “cluster analysis,” coupling it with a “decision tree model.” The first revealed groups of symptoms and progression rates that occurred together more often than would be expected by chance. The second worked out a practical, step-by-step way for neurologists to assign an individual patient to a subtype.

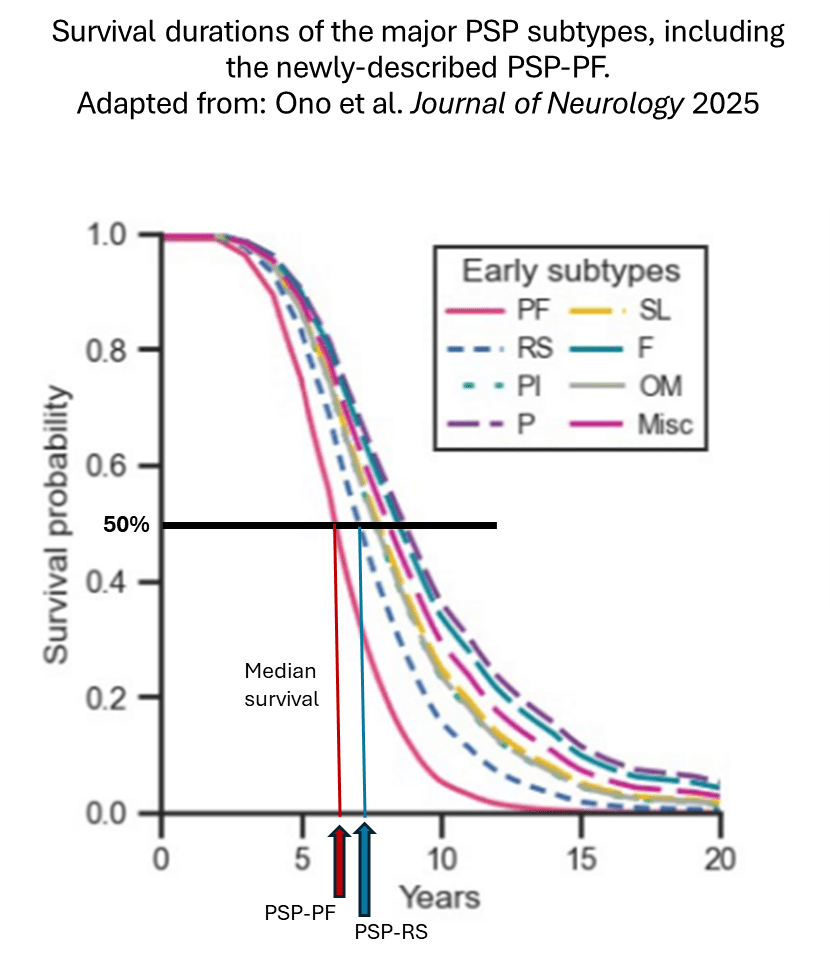

The most important result was a new subtype combining some patients with what has been defined as PSP-F with some from PSP-PI. The analysis still found statistical justification for continuing to recognize those two familiar categories as bona fide subtypes on their own. The new subtype, called PSP-PF (the continuous red curve), has the dubious distinction of having the most rapid progression and shortest total survival of all. In the graph below, you can trace a vertical line from where the “median” line crosses the curve for each subtype to find the median survival on the horizontal axis.

The median survival of PSP-PF was 6 years, with a 25-75 interquartile span (i.e., the middle two quarters of the group) of 5-7 years. This compares to PSP-RS, with a median of 7 and a 25-75 span of 6-8. For the subjects remaining in the PSP-PI and PSP-F groups, the median survival figures were 8 and 9 years, respectively.

This re-shuffling isn’t just a statistical detail. In the total group of 588 patients, 188 (32%) had PSP-PF, while only 68 (12%) had PSP-RS. Even considering the bias of any autopsy series toward over- representation of atypical cases, it’s still remarkable that PSP-PF is far more common than the other non-RS subtypes.

All that should be accompanied by the standard scientific conservatism about adopting new findings as textbook-worthy, especially without independent confirmation. Weaknesses in this study, all of which are recognized by the authors, include the following:

- When a clinical feature wasn’t mentioned in the records, the analysis treats it as if it were known to be absent.

- Quantitative data such as drug dosages, blood tests results, cognitive test results, and imaging details were not considered.

- If a symptom onset date was not mentioned in the records, the date of the first relevant physician visit was used as the equivalent.

Having recognized all that, we can still say that an AI-based procedure may have found a pattern in ordinary medical record data that human neurologists and researchers missed.

My title for this post tentatively calls the discovery “unwelcome” only because no one would be glad to learn that their subtype of PSP is more rapidly progressive than they thought. (I’m referring to those people with PSP-PI and PSP-F who would fall within the definition of the new PSP-PF.) But one upside is that the news that a large group of people with PSP has a rate of progression similar to that of PSP-Richardson could allow neurologists to better counsel patients and their families. Another important upside is that perhaps clinical neuroprotection trials could now enroll participants with both PSP-PF and PSP-RS instead of confining themselves to the latter. This could greatly increase the pool of eligible trial participants and shorten the time required for the recruitment and double-blind periods.

The main potential obstacle to enrolling participants with PSP-PF into trials is that the primary outcome measure, the PSP Rating Scale, has not yet been validated for that subtype. But that should be possible to accomplish by identifying people with PSP-PF in existing, longitudinal or retrospective observational cohorts using the decision rubric of Ono et al. Then, one would simply assess the ability of their existing, longitudinally administered PSP Rating Scale scores to track their symptoms over time.

So the “unwelcome” part of this won’t actually change anyone’s PSP for the worse and the upside of speeding up clinical trials would be most welcome.