The cerebellum is gradually being understood as a contributor to cognitive and behavioral function in both in health and disease. A new publication has teased out MRI changes in the cerebellum that differentiate PSP from other dementing disorders early in the disease. This pattern could be developed into a diagnostic test and as a marker of disease progression and even as a guide to rehabilitation measures.

The cerebellum is classically thought of as a regulator of movement. In its most simplistic essence, its job is to put a brake on voluntary movement instructions from the cerebrum. The cerebellum is guided in this task by perception of the position and motion of the trunk, head and limbs, by the effect of gravity, all complemented by visual input.

More recently, the cerebellum has demonstrated a memory function when it comes to movement regulation (making “muscle memory” more than just a metaphorical expression), and damage to certain parts of the cerebellum can cause a behavior disinhibition and cognitive impulsivity similar to the frontal lobe damage seen in PSP. In that sense, the cerebellum still functions as a “brake,” but on behavior and cognition rather than just on movement.

Now, researchers from the University of California San Francisco have carefully analyzed routine MRI scans from people with dementia arising from a variety of neurodegenerative conditions including PSP. They specifically quantified gray matter damage. (Gray matter is brain tissue composed mostly of cell bodies — as opposed to white matter, which is mostly axons. In the cerebellum, unlike the cerebrum, the gray matter is the deeper layer and the white matter is superficial.)

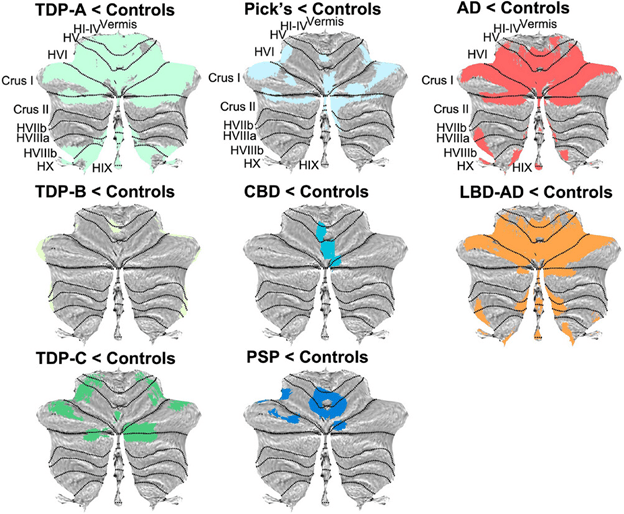

The figure below shows the principal results. Illustration from Chen Y, et al. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 2023. The senior author is Dr. Katherine Rankin. Each MRI image has been reconstructed by computer from routine scans to show the cerebellum splayed out flat. The randomly assigned colored areas represent a loss of gray matter relative to non-demented people of similar age (“Controls”). Note that the pattern for PSP differs in obvious ways from the other diseases, though at present the differences are only between the averages for groups, not individual differences useful for diagnosis in routine care.

Notes: The small type abbreviations are the sub-areas of the cerebellum. AD=Alzheimer’s disease; CBD=corticobasal degeneration; LBD=Lewy body dementia; TDP=frontotemporal dementia with TDP-43 protein aggregation. It comes in 3 types. “Pick’s” is a form of frontotemporal dementia. LBD is combined with AD because at autopsy, the former is always accompanied by some of the latter. This paper did not include Parkinson’s disease or multiple system atrophy, as those diseases rarely include dementia early in the course, the focus of the present study.

The authors conclude, “These findings suggest the potential for cerebellar neuroimaging as a non-invasive biomarker for differential diagnosis and monitoring.” They hasten to add that to understand the reasons for these different patterns of cerebellar loss, future studies will have to image the areas of the cerebrum where brain cell activity has been lost and to correlate that with corresponding loss of activity in the cerebellum. That’s called “functional neuroimaging” as opposed to the “structural neuroimaging” of the current study.

These insights, aside from their qualitative and quantitative diagnostic value, could provide guidance for electrical or magnetic transcranial stimulation (i.e., delivered across the scalp and skull rather than by inserting hardware onto or into the brain) as symptomatic treatment for PSP and the other dementing disorders.