A bit over two years ago, my posts from December 19, 2021 and January 22, 2022 reported that the drug censavudine (TPN-101) was entering a Phase 2a clinical trial. Now it’s over and the results were encouraging. I choose that word carefully, and here’s why:

The drug company sponsor, Transposon Therapeutics, presented the results at a conference in Lisbon a couple of weeks ago and I’ve only now had the opportunity to see the numbers. The trial was small (42 patients, of whom 10 were on placebo) and brief (a bit less than 6 months for the double-blind phase), with an open-label extension of the same duration. This study design is typical of Phase 2a trials in neurodegenerative diseases, which are designed to study safety and tolerability because their small size and short duration can’t detect clinically meaningful benefits.

The company’s press release says, “Participants treated with TPN-101 for the entire 48-week trial duration showed a stabilization of their clinical symptoms as measured by the PSP Rating Scale (PSPRS) between weeks 24 and 48. In contrast, participants who had been on placebo from weeks 1 to 24 continued to show a worsening of the PSPRS between weeks 24 and 48, suggesting a delay of clinical benefit onset of at least 24 weeks after start of drug treatment, and lagging behind the early effects on biomarkers seen in weeks 1 to 24.”

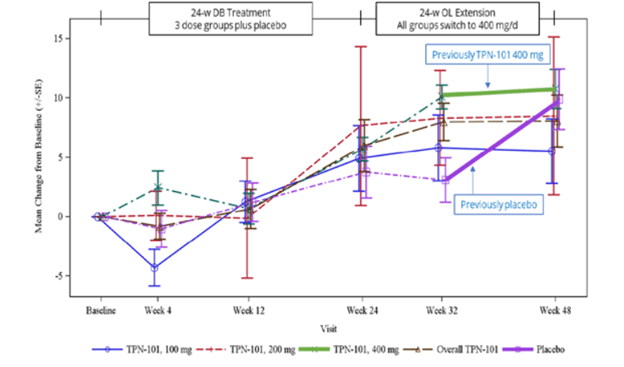

Here’s an image from the poster presented at the conference. (Sorry about the blurriness – it’s a screen shot.)

The vertical axis shows the number of points, positive or negative, by which the PSP Rating Scale changed from baseline. (Up is worse. The typical progression of PSP is 10 or 11 points per year.) The purple lines, both dashed and solid, are the patients assigned to placebo for the first 24 weeks and the other colors are the groups on the three different dosages of censavudine (100 mg, 200 mg and 400 mg per day). The brown dashed line is the aggregate of the three. The vertical line segments with hashmarks show the scores’ standard errors, a measure of variation among the patients. (See my P.S. at the end of this post.)

Note that by the end of the 24-week double-blind phase, all the results are more-or-less superimposed, meaning that the patients on active drug did no better than those on placebo. That’s normally considered a negative outcome in terms of neuroprotection, but of course this trial was too small to reveal a neuroprotective effect of realistic magnitude. After the placebo patients started receiving active censavudine at Week 24, they continued approximately along the same progressive path with the usual random wiggles (dashed and thick purple lines), ending at about 10 points worse than baseline at Week 48. This also would ordinarily be interpreted as an absence of benefit.

Now, here’s where things get tricky: After Week 32, which was eight weeks into the open-label phase, the patients on censavudine since baseline seemed to stabilize – that’s the flattening of the thick green line. In other words, their rate of progression from Week 32 to Week 48 was much less steep – a point or two rather than the expected three or four points. So, looking at the small magnitude of progression just from Week 32 to Week 48, Transposon suggested that censavudine may have a delayed benefit that became evident only after 32 weeks of treatment. In this view, the placebo group, having started censavudine at Week 24, hadn’t had enough time by Week 48 for the benefit to express itself.

Here’s the problem with that reasoning: Looking at just two visits (Weeks 32 and 48) doesn’t provide enough statistical power to conclude anything, especially with so few patients (30 patients on censavudine from the start) and only 16 weeks to work with. Furthermore, it’s easy to see that the censavudine and placebo groups, with some random wiggling, both follow the same line not only from baseline to Week 24, but also from baseline to Week 48 and from Week 24 to Week 48.

The PSPRS results were not statistically significant, of course, and Transposon didn’t claim they were. However, their presentation’s conclusions did say, “Clinical improvements emerge with longer treatment.” I say, “There’s insufficient evidence for that.”

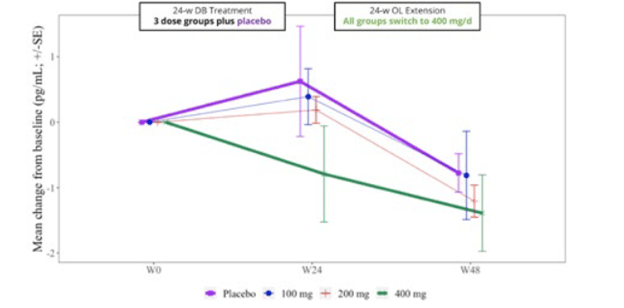

The trial included spinal fluid sampling at baseline, Week 24 and Week 48. They tested for several things, including interleukin (IL)-6, which correlates with brain inflammation, and neurofilament light chain (NfL), which correlates with loss of brain tissue in PSP. Here are the IL-6 results:

From baseline (“W0”) to Week 24, IL-6 for the group on the highest dosage of censavudine declined and continued to do so for the next 24 weeks of the same dosage. But for the groups on placebo and lower dosages of censavudine during the first 24 weeks, the IL-6 levels rose and then, after switching to censavudine (at the highest dosage), their IL-6 declined to become indistinguishable from that of the group on high-dosage censavudine from the start.

This looks very good, though I’m not sure why the placebo patients were able to “make up for lost time” so nicely. In any case, the result was not statistically significant, but at least it’s encouraging.

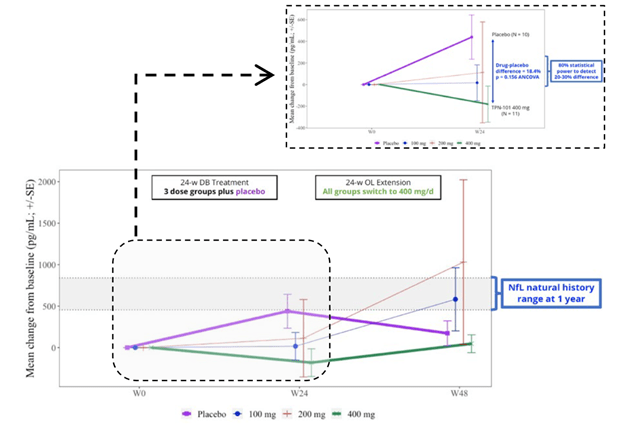

Now, let’s consider the NfL results, as shown in the graph below. In the group on 400 mg throughout, the level showed no change over the whole 48 weeks. By Week 24, the patients on placebo worsened to an extent predicted by previous research and then seemed to improve, or at least to stabilize, after starting to receive censavudine 400 mg. This result, like that of the IL-6, was not statistically significant, however. The 100 mg and 200 mg groups, upon switching to 400 mg at Week 24, seemed to accelerate in their degenerative course, a puzzling result. In any case, none of these observations reach statistical significance.

Despite the lack of statistical significance for the IL-6 and NfL results, Transposon’s bottom-line conclusions read, “Reductions in NfL and IL-6 support the potential for a positive effect on neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration.” Technically speaking, that nuanced statement is appropriate, as they do “support the potential,” but the very large titles for the two graphs above were the very non-nuanced “TPN-101 Reduces Neuroinflammation” and “TPN-101 Reduces Neurodegeneration.” I didn’t include them in my two screen shots because I didn’t want to perpetuate those very misleading declarations.

My bottom line: Censavudine (TPN-101) is acceptably safe over two years’ observation. This trial was too small and its double-blind phase too brief for any statement as to efficacy in slowing PSP’s progression. A large trial able to demonstrate whatever efficacy may exist is well justified and I look forward to it.

My other bottom line: Transposon’s presentation of its study’s efficacy results is misleading at best.

—

P.S. for the statistically interested: This presentation used standard errors (SE) rather than standard deviations (SD). SD is appropriate when two groups such as a placebo group and an active drug group are being compared. But for tracking the course over time of a single group, SE is appropriate. This presentation includes both kinds of observations, so I can’t fault their choice of SE. But you should keep in mind that the SE is a smaller number than the SD: SE is the SD divided by the square root of the N. So, in this trial, the N of each dosage group and the placebo group was about 10, and the square root of 10 is about 3, so the height of the error bars in each graph is only about a third of what most of us are used to looking at. That creates a false impression of a meaningful separation between the placebo and censavudine results.