My last post reported a study demonstrating that the genetic variants (often called mutations) conferring PSP risk interact with one another to elevate the risk beyond the simple total of their individual effects. The next day brought a publication on yet another gene associated with PSP.

The current paper’s 78 authors are in Spain, Portugal and The Netherlands. The first author, Pablo García-González, is a graduate student at the International University of Catalonia in Barcelona. The senior author is Agustin Ruiz, director of the Alzheimer research center there.

The scientists analyzed 327 Iberian and 59 Dutch patients with either PSP-Richardson syndrome or with autopsy confirmation of PSP. They excluded living people with non-Richardson variants because for a significant minority of such people, the underlying condition is not actually PSP. This is the same reason most clinical PSP trials exclude people with non-Richardson variants . The advantage is less “statistical noise” from misdiagnosis. The disadvantage is that the conclusions may not apply to all variants of PSP.

The new study compares the patients and the non-PSP control subjects using 815,000 genetic markers. Variants in the markers differ with regard to which of the four nucleotides (the “letters” of the genetic code) occurs at a specific spot in the marker gene. The markers are selected because they are approximately evenly spaced along all 23 chromosomes and occur in multiple variants in the general population, a state called a polymorphism. If the frequencies of the four nucleotides at any one polymorphic location differ between the disease group and the control group to a degree unlikely to occur by chance, we call that a statistically significant allelic association. But it’s only just that – an association, and the tricky task of proving cause-and-effect begins.

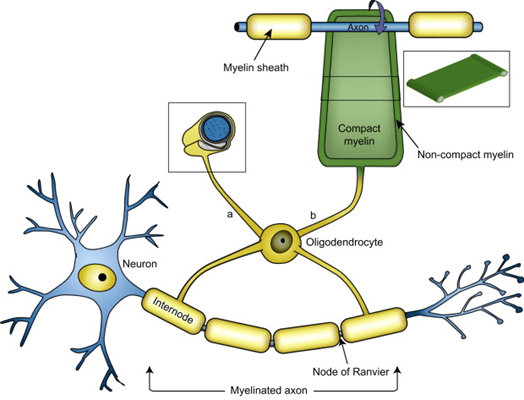

The researchers confirmed previously discovered markers and found one new one nestled between two genes called NFASC and CNTN2 on chromosome 1. The proteins encoded by both genes are involved in the function of the oligodendrocytes, a major type of non-electrical brain cell. The “oligos,” as we in the business call them, produce the insulation, called myelin, around most of the axons conducting electrical impulses among the neurons

For the statistically interested: The odds ratio for the marker’s association with PSP was 0.83, with 95% confidence interval 0.78 to 0.89 and p-value 4.15 x 10-8.

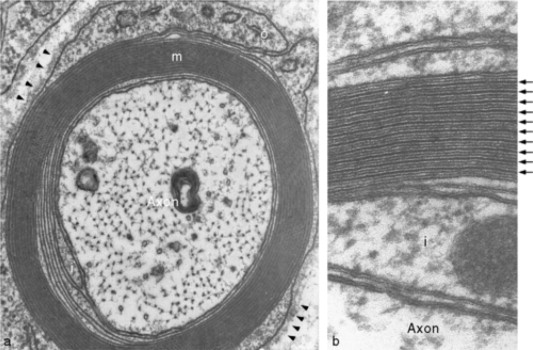

The figures below are cross-sections of a myelinated axon as photographed by an electron microscope. The lower-power view on the left shows the axon itself with its tiny organelles surrounded by the (barely perceptible at this power) layers of myelin. In the higher-power view on the right, arrows point to the myelin layers.

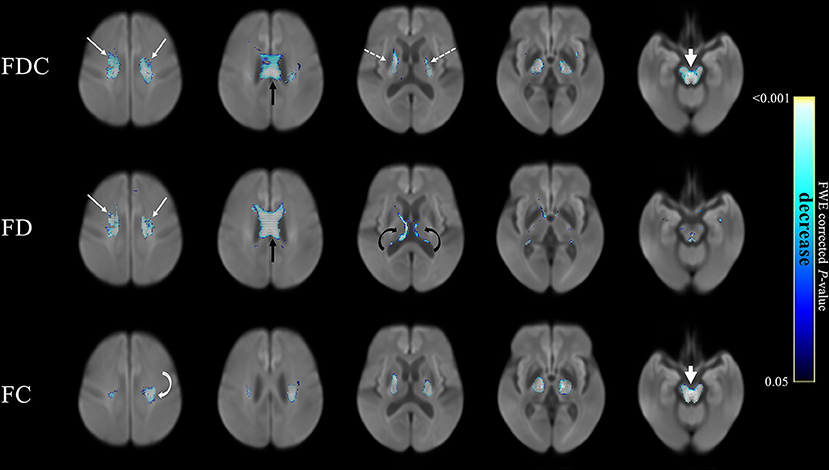

The figure below shows the extent of loss of myelin from axons in the brain as imaged by three different MRI techniques listed on the left. Each column shows a different “slice” of brain. The areas shown in blue represent areas where the myelin damage in PSP exceeded that in Parkinson’s disease. In no brain area was PD worse in that regard. The scale on the right shows how the intensity of the blue represents the statistical significance of the PSP/PD difference at that anatomical point. (From Nguyen T-T et al. Frontiers in Ageing Neuroscience, 2021.)

So, at this point, what’s the evidence for a cause-and-effect relationship between these two new risk genes and PSP? One important point is that in PSP, loss of myelin and the oligos that produce and contain it are very early and important parts of the disease process. Another is that the proteins produced by the NFASC and CNTN2 genes are “co-expressed” along with two previously-discovered PSP risk genes called MOBP and SLCO1A2, both of which are also associated with oligos and myelin. Co-expression refers to a close correlation between the amounts of multiple kinds of proteins being manufactured by the cell, implying that the proteins work together to perform some specific task required by the cell at that point in time.

The discovery of these two new PSP risk genes supports the idea that the integrity of the oligos and their myelin is a very early and critical part of the PSP process. We already know a lot about that process, thanks to decades of research on multiple sclerosis, where breakdown of myelin is even more important than in PSP, but occurs for more obviously immune-related reasons. That previous research has identified many myelin-related enzymes and other kinds of molecules that might be susceptible to manipulation by drugs. Now, it’s a matter of finding the most critical such molecules and the right drugs to return their function to something like normal.