Eye movement was the topic of the fourth of the five papers on PSP to be published on a single day last week and is the topic of the fifth as well. It’s altogether fitting and proper that on this dies mirabilis for PSP, disproportionate attention should go to the most specific single feature of PSP and the source of its name.

One of the most important early symptoms of PSP is difficulty reading that many patients describe as difficulty shifting from the end of one line to the start of the next. The problem isn’t the long leftward horizontal movement to pick up the next line, but the short downward component, and patients may report that they can’t avoid re-reading the same line. This can happen long before the neurologist’s exam can detect any loss of downward eye movement on a simple pursuit (“follow my finger”) or voluntary saccade (“look left”) test.

A group of scientists in Yonago, Japan have studied this phenomenon in a new way. Yasuhiro Watanabe, Suzuha Takeuchi, Kazutake Uehara, Haruka Takeda and Ritsuko Hanajima tracked patients’ eye movements as they read a paragraph aloud. In Japan, people are almost equally skilled at reading horizontally and vertically. Computer screen text and most books use horizontal text, while newspapers and official, formal and traditional publications are vertical. This makes Japanese people excellent subjects in an experiment comparing horizontal with vertical reading skills.

The participants included groups with PSP, Parkinson’s disease, multiple system atrophy (MSA) and spinocerebellar atrophy (SCA) as well as a group of healthy controls. For the analysis. the MSA and SCA participants were combined into one group called “spinocerebellar degeneration” (SCD).

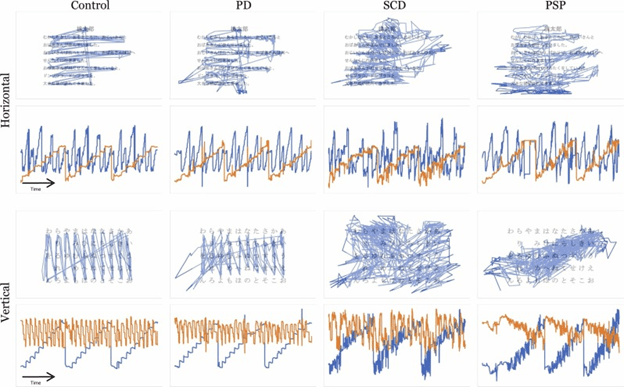

Shown below are the tracings of their eye movement during reading. The first and third rows show superimposed tracings of all 19 to 29 participants in each group. It’s obvious that the group with PSP did reasonably well with horizontal movements but had difficulty finding the start of the next line. When attempting to read vertically, those with PSP had extreme difficulty, as expected.

The second and fourth rows show eye movements over time (horizontal axis) while reading, with horizontal movements in blue and vertical movement in orange. The vertical axis shows the size of the movement. Again, for horizontal text, the horizontal movements are nearly normal in PSP, while the vertical movement is impaired. For vertical text, horizontal movement to pick up each subsequent line is moderately impaired, but the main, vertical movement down each line of characters is severely so.

The analysis used a “machine learning” procedure, a form of artificial intelligence, to create a statistical profile of the measurements for each disease group. It showed that the main difficulty distinguishing each group were downward movements in PSP, general slowness and a “stickiness” of ocular fixation in PD and poorly aimed horizontal movement with rhythmic horizontal overlying movement (“nystagmus”) in SCD. The accuracy in distinguishing controls from the patients as a combined group was 87.5%. (Accuracy combines sensitivity and specificity.) In this analysis combining the three disease groups, horizontal reading was more useful than vertical reading. Using vertical reading, PSP was readily distinguished from SCD (accuracy 91.4%) but not as well from controls. Nor did it do well in distinguishing PSP from PD despite appearances in the tracings shown above.

The authors feel that this technique could be improved in various ways. They did correct the results for overall cognitive performance using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), but perhaps a correction for overall neurological disability, or at least dysarthria (in this reading aloud task) could be added. I’d further suggest that to remove most of the cognitive and speech components of reading, the task could be reduced to reading a series of single digits rather than text sentences. This could also allow the test to be used in populations not as skilled as the Japanese in reading text vertically.

A major virtue of this test is that after the one-time, initial software development, it’s very inexpensive, convenient and non-invasive. It could be implemented on a desktop computer screen or perhaps on a tablet (a phone screen might be too small). If we’re trying to detect people with PSP in a very early stage to test a new drug — and eventually to receive a prescription for it — a widely applicable, remotely administered screening test like this could be just the ticket.

We don’t yet know the sensitivity of this test to PSP progression over time, but if it proves useful in that regard, perhaps it can be used as an outcome measure in treatment trials or as a way for neurologists to monitor their patients’ illness and offer prognostic advice.