In medical school, we were taught, “If you hear hoofbeats, consider horses, not zebras.” While it’s true that more common diseases are more likely in a given situation, occasionally rare things do occur. A great example is Wilson’s disease, because it’s a “zebra” that’s highly treatable, and failure to diagnose and treat it could be devastating.

Wilson’s is quite rare — a bit less than half as common as PSP. It usually starts during late childhood, but occasionally does so as late as age 55. It’s caused by a mutation in a gene related to the metabolism of copper, which accumulates in parts of the brain and in the liver to toxic effect. It causes a long and variable list of neurological symptoms and can occasionally mimic PSP to a degree. That’s why our 2024 review called “A General Neurologist’s Practical Diagnostic Algorithm for Atypical Parkinsonian Disorders” included Wilson’s among the 64 conditions (most of them zebras) to be considered in such situations.

Untreated Wilson’s disease typically leads to death from liver failure within a few years of diagnosis. But drugs that remove copper from the body or that address the problem in other ways are extremely effective and if started soon enough, can confer a normal lifespan with little or no disability. Furthermore, Wilson’s is easy to test for.

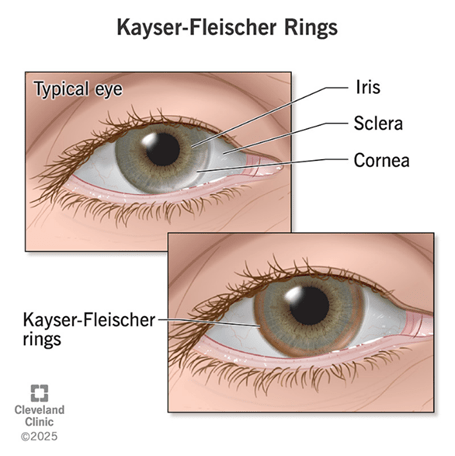

I was reminded of this by a case report appearing today in the Annals of the Indian Academy of Neurology authored by Drs. J. Saibaba, S. Gomathy, R. Sugumaran and S Narayan. Their patient’s symptoms started at age 51 with unprovoked backward falls followed by general slowing, slurred speech, tremor, weight loss, and depressed mood. (Any of that sound familiar?) His exam showed, among other things, impairment of downgaze, limb rigidity, and loss of balance. He also showed two strong clues for Wilson’s disease: a coppery-brownish ring at the edge of his corneas called a “Kaiser-Fleischer ring” and an unusual tremor of the arms called a “wing-beating tremor.”

Most neurologists test for Wilson’s in anyone with any movement disorder starting before age 55 without other obvious cause. The testing consists of a check for K-F rings, which may require a “slit lamp” exam by an ophthalmologist; a blood test for a protein called “ceruloplasmin;” and a 24-hour urine collection to check its copper content. If those are inconclusive, then a liver biopsy and/or a genetic test can be performed.

The important take-home is that if what looks like PSP starts before age 55, especially if accompanied by liver disease, Wilson’s disease should be tested for. The result could be life-saving.