I’ve not posted much in a while. Lots of other commitments, but unlike this blog, they had deadlines, you see. So, I have lots to catch you up on, starting with a cool study in zebrafish. This cute, 1-2-inch fishy is a popular aquarium pet. As it turns out, it also makes a great animal model for PSP.

The model is created by injecting a normal human tau gene into a fertilized fish ovum. Human tau comes in six different versions, called isoforms. The tau gene used here encodes only the single isoform that accumulates in the neurofibrillary tangles of typical, non-hereditary PSP, called 0N4R tau. The resulting adult fish not only swims poorly — its eyes don’t move very well, either. It can then be bred to form an ongoing colony. Compared with mice, the leading PSP model until now, zebrafish are cheaper and easier to maintain and provide a much more efficient way to screen dozens of drugs quickly.

The figures below are from a new publication from the University of Pittsburgh led by senior author Dr. Edward A. Burton with first author Dr. Qing Bai.

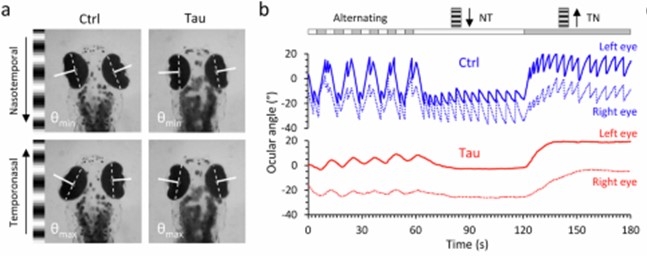

Panel A shows still images from a video of a zebrafish as seen from above. The large, dark ovals are eyes and the smudge toward the bottom is the body. Panel B shows the movements of the eyes when shown a moving array of black-and-white stripes. The blue tracing is from a fish without the added human tau gene. Its eyes move crisply from one stripe to the next, but the red tracing, from a fish with the human tau gene, shows a weak response. This is identical to the response in people with PSP who are asked by a neurologist to count the stripes on a strip of cloth moved across their field of vision. It’s called “opticokinetic nystagmus” and is a good way to detect the earliest, asymptomatic involvement of the eye movements of PSP or some other disorders.

If you go to the link provided above and scroll down to the link for “Supplementary movie 1,” you’ll see a video of the eye movements and the stimulus stripes.

Armed with this experimental set-up and another to trace traced the fish’s spontaneous swimming in a circular dish, Drs. Bai and colleagues then screened a panel of 147 chemical compounds for any ability to correct the problems. The 147 were chosen because of their ability to modulate the attachment of small molecules to genes, one type of “epigenetic” alteration that we know occurs in PSP. Large drug screens in vertebrates are much more easily performed in zebrafish than in mice.

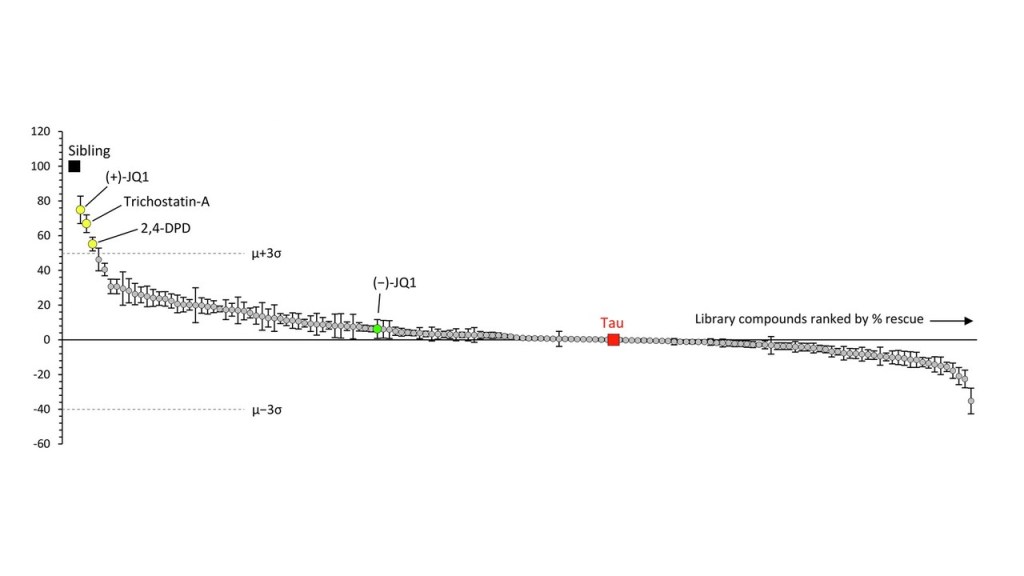

The graph below shows the results. Each circle is one drug and the vertical axis is the improvement or worsening it produces in the zebrafish. The “whiskers” on each circle indicate the variation among the 12 fish tested on that drug. The drugs’ results are displayed left-to-right in descending order of benefit, which means that the drugs on the right, below the “0” line, were actually deleterious. The black square labeled “sibling” indicates a littermate fish without the human tau against which the drugs’ effects are compared. The red square labeled “tau” shows another kind of comparators — the fish with human tau that were left untreated. The dotted, horizontal lines are placed at a point three standard deviations (σ) from the average (μ) of the 147 drugs’ degree of benefit (upper line) or worsening (lower line). That’s the researchers’ threshold of significant interest for the drugs.

The best-performing drug was something with the weird name, (+)-JQ1. It’s a member of a group called “bromodomain inhibitors,” which have nothing to do with the element bromine. A bromodomain is a string of 110 amino acids that forms part of many proteins involved in regulating the transcription of certain genes into their own proteins. Other inhibitors of bromodomain-containing proteins are being tested as treatment for various cancers. My clinicaltrial.gov search on “bromodomain inhibitor” produced 52 such trials, though none so far for (+)-JQ1 itself. The second-best bromotomain inhibitor emerging from the zebrafish screen is trichostatin-A, a non-FDA-approved, anti-fungal antibiotic with potential anti-cancer properties and 137 listings in clinicaltrials.gov. Third is 2,4-OPD, on which I found no information anywhere.

Bonus fact for the real science nerds: The graph shows a green data point for (-)-JQ1. That’s the “enantiomer” of (+)-JQ1. Enantiomers are pairs of molecules with identical sets of atoms in mirror-image configurations. Some such pairs have identical properties but many don’t. A good example of the latter is levodopa, the (-) version of dihydroxyphenylalanine. It helps Parkinson’s dramatically and PSP modestly, but the (+) version, which would be called “dextrodopa,” does neither. The “dextro-” and “levo-” prefixes refer to the clockwise or counterclockwise rotation that a solution of the compound imparts to the plane of polarized light.

So, let’s await experiments of (+)-JQ1 and trichostatin-A in other models such as tau knock-in mice, stem cells and organoids. Let’s also await screens of other classes of drugs in the cute little zebrafish that provide a great new, efficient test bed for PSP treatments.

Thank you very much, Dr. Golbe, for taking the time to share this explanation. The zebrafish-based research is fascinating. We wonder how this particular creature was chosen? We are also happy that you mention that you have lots to catch us up on as we’ve missed your posts!

Referring to this August 23, 2024 article in Science entitled “Restoring hippocampal glucose metabolism rescues cognition across Alzheimer’s disease pathologies”, are you familiar with any work involving ID01 inhibition and PSP? It’s probably a stretch, but we note that, interestingly, (+)-JQ1 and ID01 both seem to be involved in some way in brain glucose metabolism.

All the best.

Maura & Pedro

Hi, mauraelisabeth3:

The zebrafish was chosen because it’s easy to manipulate genetically. Like any small fish, its bodies are close to transparent when they’re young, facilitating certain experiments. It’s also hardy and reproduces quickly.

Regarding your question about ID01 inhibition and PSP, I asked Dr. Burton, and here’s his unedited answer: “The metabolism question is interesting. The paper cited in the question shows that APP and Tau both activate kynurenine synthesis which inhibits glycolysis in astrocytes (a significant source of neuronal ATP). The only literature related to our work that I am aware of is a study in acute lymphocytic leukemia cells in which glycolytic enzymes were downregulated by (+)JQ1 exposure. Not sure how this relates to neurons and glia in vivo, although activated microglia switch from OxPhos to glycolysis so this might be one mechanism underlying our observations. One of the issues with a reductionist in vitro approach is that targeting a single regulatory protein can cause multiple apparently conflicting consequences in different experimental systems and it is unclear which is dominant or important in the brain. Screening in vivo embraces this complexity and asks a more pragmatic question – what works? We are currently working out the biology mediating our new observations and will hopefully have data explaining the mechanism soon.”

Thank you, Dr. Golbe, for sharing Dr. Burton’s insights. Separately, I happened to come across this article describing another Zebrafish-based research study aimed at treating Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative conditions. Researchers in the UK report that an existing drug for the treatment of Glaucoma, Methazolamide, reduces levels of tau in the brain and protects against its further build-up. Following promising results from their Zebrafish study, the researchers replicated these results through testing in mice. Quoting from the article: “Methazolamide is a type of drug known as a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, which stops the activity of an important enzyme involved in regulating acidity levels in our cells. This in turn forces the cells to “spit out” the tau proteins, almost like they are having their stomachs pumped.”

I do not find explicit mention of Methazolamide in Dr. Burton’s paper, but wonder whether he might have considered testing this already approved drug, and whether it may have potential for treating PSP? Thank you as always for your thoughts.

Maura & Pedro

Hi, ME3: I saw that paper and was working on what would become my 11/3/24 post when your comment arrived. Congrats again on your sharp eye for what’s new and important. Dr. G