Yesterday’s post was about the clinical heterogeneity of PSP and how it prompts a theory about the cause(s) of the disease. A couple of hours after I hit “send” I saw a new paper that indirectly supports my idea.

As you probably know, PSP comes in ten known subtypes. The original type, first described in detail in 1963, is called PSP-Richardson syndrome and accounts for about half of all PSP. The other nine have been described since 2005. The new paper reports five subtypes among PSP-Richardson syndrome itself.

The study is from Dr. Mahesh Kumar, a post-doc at the Mayo Clinic, with Dr. Keith Josephs as senior author. They performed statistical tests called “network analysis” and “cluster analysis” on their 118 patients with PSP-Richardson. The five PSP-Richardson “sub-sub-types” emphasize, respectively, tremor; light sensitivity; reduced eye movement (i.e., supranuclear gaze palsy); cognitive loss and slowness/stiffness.

These are not just points on a continuous spectrum. Rather, in each of the five PSP-Richardson sub-sub-types, a group of features and their severities occurs together in individuals in a combination that would not be expected by random combination based their respective frequencies in the total PSP-RS population. For example, people with worse slowness/stiffness tended to have milder eye movement problems and worse cognition than chance would dictate.

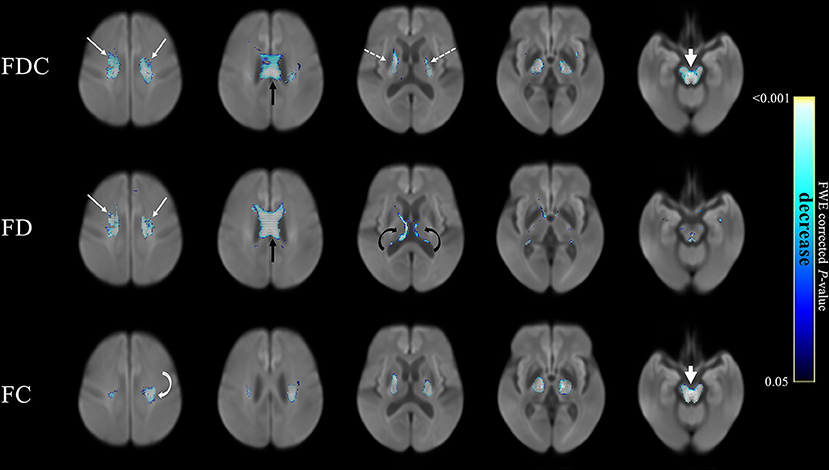

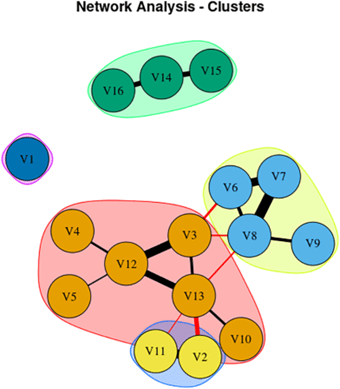

Here’s a graphical representation of the results. The features represented by the circles in each group interact with one another in a mutually reinforcing (the black bars) or interfering (the red bars) way. The thickness of the bars represents the strength of the interaction. An explanation in the researchers’ own words follows:

From Kumar et al. Mov Dis Clin Prac 2025

Network Analysis showing 16 signs/symptoms and their associations. Each node in figure represents symptom/sign, Black edges represent positive connection, and red edges represent negative connection; thicker edges represent stronger association.

V1, Sensitivity to bright light; V2, MoCA (Cognition Score); V3, Neck Rigidity; V4, Urinary Incontinence; V5, Emotional Incontinence; V6, Upward ocular movement dysfunction; V7, Downward ocular movement dysfunction; V8, Horizontal ocular movement dysfunction; V9, Eye lid dysfunction; V10, Limb apraxia; V11, FAB (Executive Score); V12, Gait dysfunction; V13, Bradykinesia; V14, Postural tremor; V15, Kinetic tremor; V16, Rest tremor.

All this begs the question as to the basis of the specific groups of signs and symptoms. The answer will probably apply as well to the ten PSP subtypes as to the five PSP-Richardson sub-sub-types. It probably has to do with the specific combination of PSP’s menu of causative factors at work in the individual. As I pointed out in my last post, there are 14 known gene variants contributing to PSP risk and that number is growing. Exposure to toxic metals may also be a factor and those exposures could come at different times of life and in various durations, intensities and combinations. The number of genetic/toxic combinations of these factors sufficient to cause PSP would be astronomical, and the likeliest combinations might account for the likeliest PSP subtypes and sub-sub-types.

Then throw in the stochastic factors, meaning random throws of the dice. I’ll get to that in a future post.