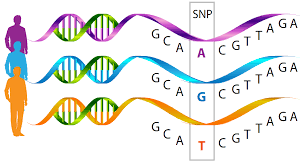

The first PSP whole-genome analysis (or WGA) was published in 2011. It found that “markers” associated with each of four genes were more common among people with PSP than among controls without PSP. Those markers were themselves genes of precisely known location on their chromosome but with unknown or irrelevant function. Such a gene is useful as a marker if one specific nucleotide (the A’s, T’s, G’s and C’s of the genetic code) varies among healthy individuals. Such a phenomenon is called a “single nucleotide polymorphism” or SNP, pronounced “snip.”)

So, for example, at a certain location on, say, chromosome 1, the general population might have an A in 70% of people, a T in 20%, a G in 8% and a C in 2%. If that array of frequencies is different (to a statistically significant degree) in the population with a certain disease, it means that the marker gene is located very close to (or sometimes even within) a gene that’s actually contributing to the cause of the disease.

Since then, it has become possible to easily work out the sequence of nucleotides in every gene, which, as you’d imagine, can make it a lot easier to find genetic causes of diseases. But it’s not as easy as it sounds because it’s hard to distinguish a harmless copying error from a disease-causing error. Besides, the statistics required for sequencing studies have not yet been fully invented. So, good old marker analysis is still very important and useful.

Now let’s talk about the cause of PSP. There seems to be some sort of genetic predisposition that increases the risk but is probably not enough to actually cause the disease within a usual human lifespan. So, something else, presumably an environmental exposure, is probably needed. The only such candidate toxins discovered to date for PSP have been metals, though specific metals have not been clearly identified. (There’s also unconfirmed PSP risk for consumption of paw-paw, a fruit harboring a mitochondrial toxin; and well-confirmed incrimination of lesser educational attainment, though how that relates to environmental toxins or to PSP is unknown.)

Each of those four genes identified in 2011 and about 14 others discovered since raises the risk of PSP by only a tiny amount – in the neighborhood of 1-2%. But that figure was calculated separately for each gene. There has been no attempt to work out how the risk genes might interact to raise the PSP risk enough to allow the disease process to get started, with or without an extra boost from some mysterious environmental exposure.

Still with me? I hope so, because I’ve finally gotten to my point.

The current issue of Journal of Neurogenetics includes a paper from a research group in Bangalore, India headed by Dr. Saikat Dey of the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, with senior author Dr. Ravi Yadav. They looked only at those original four genes identified in the 2011 whole-genome marker analysis, called MAPT (encoding the tau protein), STX6 (encoding for syntaxin, which directs the movement of tiny chemical-filled balloons called vesicles in brain cells), MOPB (encoding myelin basic protein, a component of the layer of insulation around axons in the brain), and EIF2AK3 (encoding PERK, a protein that helps regulate the stress response in brain cells).

Dey et al looked for combinations of these genes’ markers occurring at a greater frequency in PSP than expected by chance given their individual frequencies. (This is called “epistatic” gene interaction.) The strongest result was between MAPT, STX6 and MOBP. The interaction between MAPT and MOBP was almost as strong, and slightly weaker interactions occurred between MOBP and STX6 and between MOBP and MAPT.

So what, you say? This is important because it can explain how gene variants, each of which raises the likelihood of developing PSP only very slightly, can nevertheless cause the disease if they occur together, perhaps even without any ancillary environmental toxin.

This can explain why PSP and other neurodegenerative diseases generally run only weakly in families: It’s unlikely that any two close relatives will share the same combination of gene variants that raise PSP risk.

Here’s a general illustration of what I’m talking about: Suppose a disease occurs with 100% likelihood in anyone with a risk mutation in each of three specific genes and that each mutation by itself has a frequency of only 1% in the population. That means that for someone to develop the disease, they’d need the unlucky combination of three 1% events. That likelihood is 1% to the third power, or 1 in a million. Now, that person’s sibling would have only a 50% chance of sharing the same form of each gene (called an “allele”). So, for each sibling of the person with the disease, the chance of sharing all three disease-causing alleles would be 0.5% to the third power, or 1¼ in 100 million.

Such gene interactions explain how a purely genetic disease could so rarely occur twice in the same family.

I’ve simplified the analysis of Dr. Dey and colleagues, and more important, there are at least another 10 PSP risk genes that their analysis didn’t consider. So, I hope they or someone else gets around to that very soon. Maybe they will find that the cause of PSP can be entirely explained by unusual combinations of mildly risk-conferring genes that can be tested for in a drop of saliva. That has some important ethical implications, but it could permit genetic counseling and could make it much easier to find volunteers with “pre-PSP” on whom to test drugs to slow or halt the disease’s progression. Furthermore, identifying a combination of protein actions that, when deficient, causes PSP could permit targeted design of new drugs.