Back in the 19th Century, diagnosing brain disorders relied mostly on listening carefully to the patient’s history, performing a detailed neurological examination, and knowing what previous, similar patients turned out to have at autopsy. That approach remains important, but since the early 20th Century, chemical, electrical and imaging tests have replaced it to a great extent. But now, neurologists at one of the world’s most prestigious medical centers, the Queen Square Institute of Neurology at University College London, have turned back the clock.

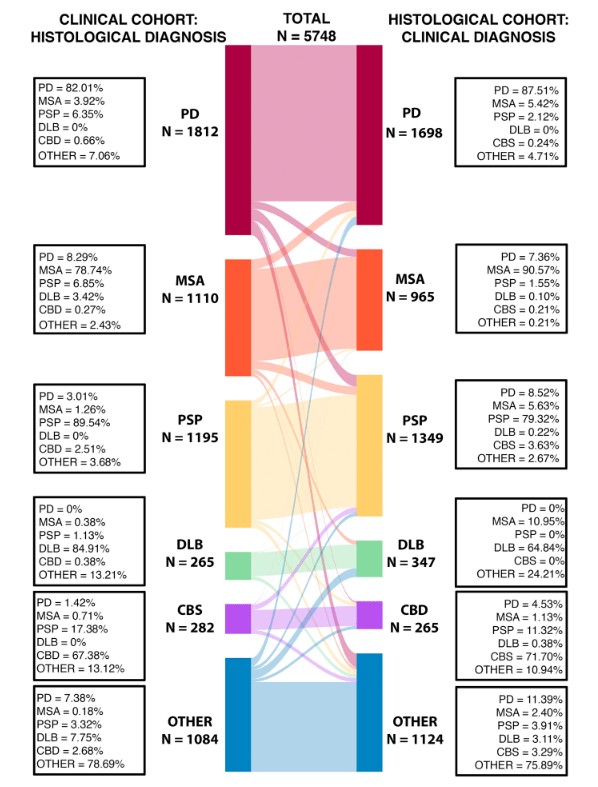

The researchers were motivated by the failure to date of modern techniques short of autopsy to provide a sufficient level of diagnostic certainty for the atypical Parkinsonian disorders. So, they squeezed some more value out of the traditional approach. First, they reviewed 125 publications since 1992 describing a total of 5,748 people with Parkinsonian disorders of various types and a diagnostic answer at autopsy. Those proven diagnoses were Parkinson’s disease (30%), PSP (23.5%) multiple system atrophy (16.8%), dementia with Lewy bodies (6.0%), corticobasal degeneration (4.6%). There was also a large group called “others” (19.6%), who mostly had Alzheimer’s disease, which in its advanced stages can acquire stiffness and slowness and look “Parkinsonian.” Keep in mind that the sources of these numbers were specialized academic referral centers, where the atypical Parkinsonian disorders would be over-represented.

Led by first author Dr. Quin Massey and senior author Dr. Christian Lambert, the researchers invented a new statistical technique called “metaphenomic annotation,” which involved feeding the 125 journal articles into commercially available text-mining software to tabulate the patient’s lists of symptoms against the autopsy results.

Etymology lesson of the day: “Meta” means “beyond,” in this case beyond the confines of a single published study. “Pheno” means “outward appearance,” in this case the features of the disease during life. “Phenomics” means a large collection of such features, analogous to “genomics” as a large collection of genes. “Annotation” in this case means somehow managing to shoehorn all that data from disparate sources into a usable database.

They found that among the 1,195 people with PSP diagnosed during life, the autopsy diagnosis was PSP in 89.5%, PD in 3.0%, CBD in 2.5%, MSA in 1.3%, and “other” in 3.7%. Among the 1,349 people whose autopsy showed PSP, the diagnosis during life was PSP in 79.3%, PD in 8.5%, MSA in 5.6%, CBS in 3.6%, DLB in 0.2% and “other” in 2.7%. The graph below shows the corresponding numbers for all five conditions and the “others” group. The curving bands show how the diagnoses made during life (the “clinical cohort” on the left) were corrected by autopsy to the diagnoses (the “histological cohort” on the right). (“Histology” is the study of body tissues through the microscope.)

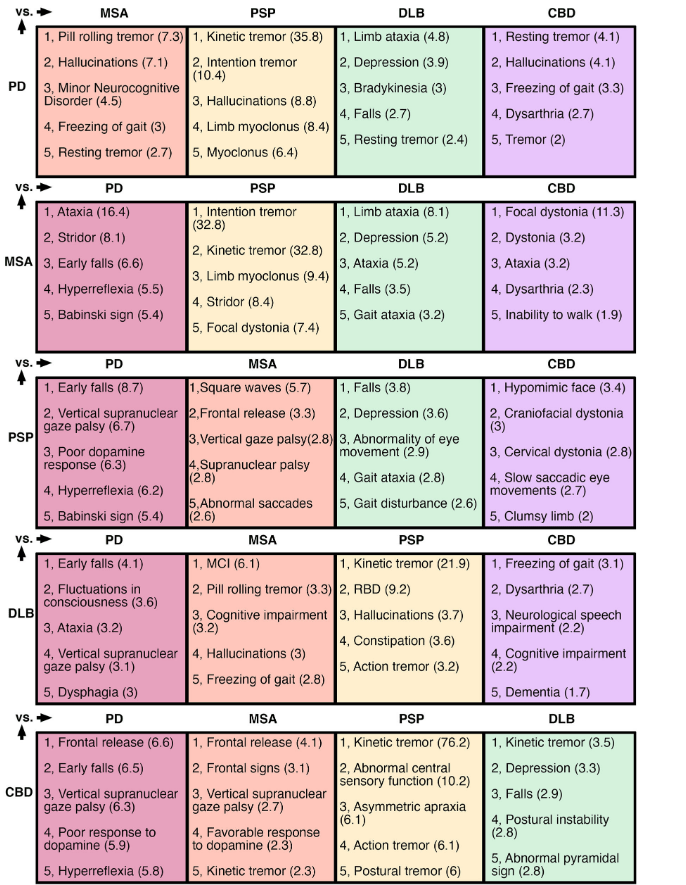

Figure and table from: Quin Massey, Leonidas Nihoyannopoulos, Peter Zeidman, Thomas Warne, Kailash Bhatia, Sonia Gandhi, Christian Lambert. Refining the diagnostic accuracy of Parkinsonian disorders using metaphenomic annotation of the clinicopathological literature. NPJ Parkinsons Disease 2025 Nov 10;11:314.

If you think the figure above is information-rich but a bit confusing, the table below may be more of both. Each of the five rows is labeled with a disease defined by autopsy, and each column represents how that disease compares with each of the other four with regard to diagnostic signs during life. For example, for assistance in distinguishing PSP from MSA, look at the third row, second column, where square waves (an abnormal eye movement) are listed as being more common in PSP. The number in parentheses is the ”positive likelihood ratio” for distinguishing PSP from MSA. The PLR is calculated as (sensitivity / (1-specificity)) and can be informally described for this example as how much more likely is PSP than MSA to be the correct diagnosis, based on just this one diagnostic feature.

This analysis can be very useful for the vast majority of neurologists and mid-level neurological professionals unfamiliar with the details of the differences among the atypical Parkinsonian disorders. Even experienced movement disorders neurologists will find it useful to have all this information in one place and neatly quantified.

A great part of this project is that the researchers have made the annotated data and their computer code publicly available for the use of other researchers.

Hi Dr. Golbe

Hope you are doing well. I regularly follow your blogs which help me to understand PSP better. I am very active on Facebook where I write posts and comments in English (6 groups) and in Croatian (3 groups). I would very often like to share information from your blogs with all groups, especially groups in Croatian because there is no serious information in those groups. Do you allow me to share your information, if so in what way?

Best regards,

Branko

Hi, Branko:

I’d like to reply to you by email rather than to share my technological ignorance in public, but the email address I have on file for you is not working. Please email me directly. Thanks.

Larry