What’s really fun about blogging is that I can express scientific or medical opinions without having to get past experts like peer reviewers, journal editors or conference organizers. (Hence most of the evil trash on the Internet.)

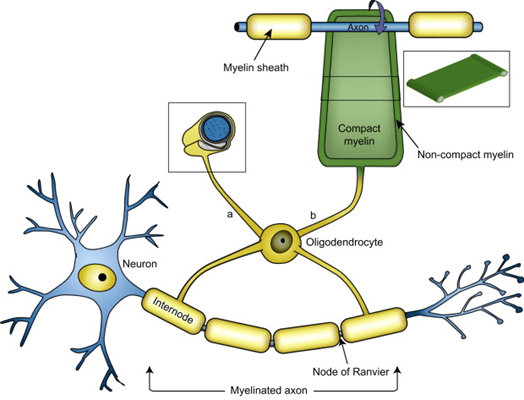

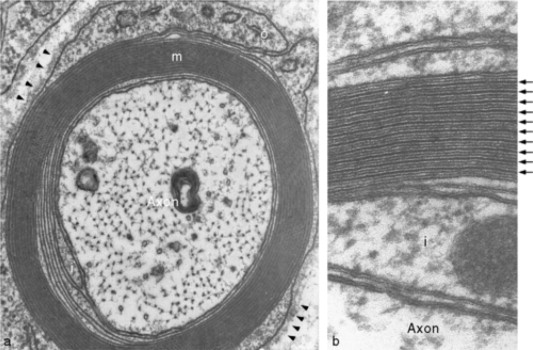

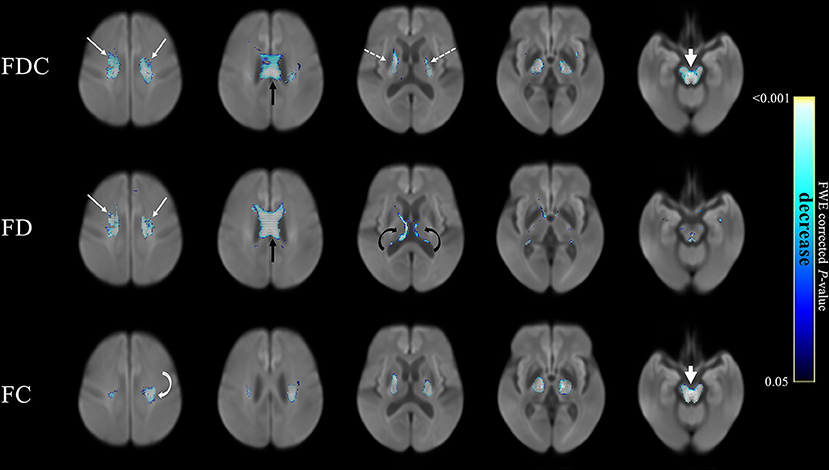

But a frequent, insightful commenter called “mauraelizabeth3” asked this question after reading my last post about a new genetic finding in PSP incriminating to the myelin-producing cells, the oligodendrocytes, as a major possible starting point for PSP.

Is it known how these findings relate to (or perhaps result in) the hyperphosphorylated tau protein that aggregates in the brains of PSP patients?

I’ll respond to that excellent question with my own current theory of the etiology and pathogenesis of PSP. It’s based on legit science, but of course, I don’t really know how much emphasis to place on each of the disparate current facts, or how many additional facts await discovery.

Dear me3:

That’s really the question, isn’t it! My own formulation at this point is that the loss of myelin from those multiple gene variants is a sideshow that impairs neurological function but isn’t actually part of the cause of PSP. Instead . . .

- I’d propose that the first abnormal event is some inherited or de novo mutations or epigenetic alterations in the MAPT gene (which we know do exist in PSP) changes the structure or the post-translational modifications of tau in a way that stimulates its hyperphosphorylation as a reaction designed to facilitate its degradation. Hyperphosphorylation tau might also be the result of some sort of toxin exposure, with metals currently the leading contender.

- Then, hyperphosphorylated tau falls off the microtubules and is free to do mischief all over the cell. Maybe the first (or only) thing it does is to make the genomic DNA in the nucleus lose some of its protection against inappropriate transcription into RNA. It’s been shown that such inappropriate transcription allows retrotransposons to be transcribed. (Those are pieces of DNA implanted there by viruses millions of years ago. They have reproduced themselves to other parts of the genome and now account for about 40% of our DNA.)

- The RNA so produced is recognized by the immune system as viral. An immune response ensues, which attacks and degrades a lot of RNA and innocent bystanders. The resulting molecular garbage is a major challenge for the cell’s regular garbage disposal, the ubiquitin-proteasome system and the autophagy/lysosomal system.

- Meanwhile, all that hyperphosphorylated tau is misfolding and then aggregating with itself. This does take place under normal, healthy conditions to some extent, and the disposal systems can handle that. But now, with the garbage from the inflammation and the unusual amount of aggregated tau to degrade, the garbage disposal is overwhelmed. This allows all sorts of normal toxic garbage to accumulate, and that’s eventually fatal to the cell.

- This whole process starts in the astrocytes or oligodendrocytes and spreads to the neurons courtesy of the microglia (the brain’s immune cells), synaptic connections and direct contact.

Keep in mind that I’m a clinician with little laboratory experience beyond delivering fluid samples from my patients to my smarter colleagues with the pocket protectors. But I try to keep up with the latest in all aspects of PSP, and there’s lab support for all of the assertions in my hypothesis. It’s just that putting those facts together is tricky, like cracking a complicated criminal plot. I hope that my hypothesis at least illustrates that we’re starting to get more of a handle on the pathogenesis of PSP.