I want to tell you about one small study that, although it needs expansion and confirmation, is exciting because it could allow a future PSP neuroprotective treatment to be prescribed before having to wait for symptoms to appear.

You’ve probably heard of the protein “alpha-synuclein” (pronounced “suh-NOO-klee-in”). It has a long list of normal functions in our brain cells, but in its various misfolded forms, is the major component of abnormal protein aggregates of Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and multiple system atrophy. Now, a blood test for alpha-synuclein might actually provide a way to diagnose PSP despite the fact that tau, not alpha-synuclein, is PSP’s abnormally aggregating protein.

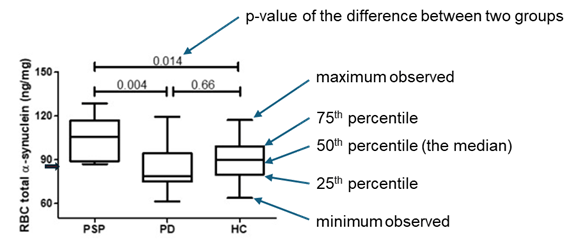

The new paper in the journal Biomedicines by researchers at the University of Catanzaro in Italy, have found the concentration of alpha-synuclein to be slightly greater in the red blood cells of people with PSP than in healthy people or those with PD. The graph below from the journal article (with my explanatory notes and arrows) compares results from the eight people with PSP to 19 with PD and 18 healthy control participants. The vertical axis is alpha-synuclein concentration expressed in nanograms of alpha-synuclein per milligram of red blood cells.

One paragraph of technical background on alpha-synuclein: While alpha-synuclein does most of its work in brain cells, helping in neurotransmitter release and protect against mis-application of the cell’s “suicide” program (called “apoptosis”), it’s also abundant in red blood cells. In fact, it’s the second-most-abundant protein in red cells after, of course, hemoglobin. The job of alpha-synuclein there is to help to stabilize their red cells’ outer membranes and to help in the process of removing the nucleus from the red cells’ precursor cells in the bone marrow. Nucleus removal makes more room for hemoglobin and more important, allows the cells to deform more easily as they pass through capillaries. That deformation provides a signal to the hemoglobin to release their oxygen to the tissue.

Back to business: The graph shows clear overlaps between PSP and the other groups, but the medians do differ to a statistically significant degree. The short arrow by the vertical axis points to a value of 85.06 ng/mg, which the researchers chose in retrospect as the best cutoff between normal and abnormal. Using that definition, the sensitivity of the measure was 100%, meaning that all eight participants with PSP had an abnormal result (that is, a value higher than 85.06). The same cutoff yielded a specificity of 70.6%, which is the fraction of the PD and HC participants with a normal result; in other words, the fraction that would be diagnosed correctly as “non-PSP.”

But if only 70.6% of the participants with “non-PSP” have a normal test result, that means that the other 29.4% have an “abnormal” result and would be falsely diagnosed with PSP. PD is about 20 times as common in neurological practice populations as PSP, so for every 1,000 patients who might have PSP or PD and see a neurologist, about 50 have PSP and 950 have PD. If you do the red cell test in all 1,000, that means that 29.4% of 950, or 279, will have an abnormal result. If all 50 with PSP also have an abnormal result, that totals 339 people with abnormal results, of whom 279 (a whopping 82%) don’t actually have PSP.

So, a neurologist seeing a result below that 85.06 cutoff would be able to reassure patient that they do not have PSP, with, of course, the usual precaution that outliers and lab errors do exist. A result above the 85.06 cutoff would prompt other diagnostic tests with greater specificity, although probably with greater expense, inconvenience and/or discomfort. I hasten to add that like any new research finding, this needs confirmation by other researchers using other, larger patient populations in all stages of illness.

You may recognize this result as the definition of a “screening test.” That’s a relatively inexpensive, convenient, safe and sensitive test suitable for use in large populations of asymptomatic or at-risk people. If a screening test is positive, further testing, or at least close observation, is advised. A good example is a routine mammogram, where a negative reading is great news and a positive reading prompts further testing. In this example, that testing usually results in a diagnosis of a benign cyst or scar or something else other than breast cancer, and the few women whose mammogram abnormalities turn out to be breast cancer and whose lives are saved by the ensuing treatment will be very glad to have had that screening test. A similar situation could develop for PSP once we have an effective way to slow or halt progression of the disease. That’s what the PSP neuroprotection trials currently under way hope to accomplish.

It seems unlikely from the new data that red cell alpha-synuclein concentration would ever offer enough specificity to diagnose PSP to the exclusion of non-PSP. But people with a positive test could then have, perhaps, an MRI, where certain arcane measures of the midbrain and basal ganglia could provide diagnostic information with the specificity for PSP that’s missing from the red cell alpha-synuclein test. In this way, the red cell alpha-synuclein is similar to neurofilament light, a protein elevated in the blood and spinal fluid in PSP but also in several other neurodegenerative diseases.

The senior author of the new paper is Dr. Andrea Quattrone, whom I know well and can vouch for. He is an internationally recognized leader in discovering diagnostic markers for PSP. The first-named author is Dr. Costanza Maria Cristiani.

More technical stuff in italics: Why should alpha-synuclein occur in elevated amounts in a tau-based disorder like PSP? Cristiani et al hypothesize that the red cells absorb most of their alpha-synuclein from the plasma (the liquid component of the blood) rather than being “born” with it in the bone marrow. They cite previous findings that excessive tau protein impairs the blood brain barrier, which could allow alpha-synuclein, an abundant protein in the brain, to leak into the blood, where it’s “scavenged” by the red cells. An obvious next step is to check other tauopathies such as Alzheimer’s disease for elevated red cell alpha-synuclein.

And now, on a personal note: My career as a researcher started in Parkinson’s disease and for a decade starting in 1986, I led the clinical component of the project that discovered that alpha-synuclein was related to PD. It began when I found and painstakingly worked up a large family with a rare, strongly inherited form of PD . That work, which included many collaborators I recruited in multiple institutions and countries, showed that family’s illness to be caused by a mutation in the gene encoding alpha-synuclein, which had not previously been suspected of any relationship to PD. Soon thereafter, others found alpha-synuclein as the major constituent of Lewy bodies (the protein aggregates of PD) in individuals with ordinary, non-familial PD without the mutation. Now, alpha-synuclein treatments and diagnostic tests are being developed for PD. So, if a critical diagnostic test for PSP, the disease to which I’ve devoted most of the more recent decades, should turn out to be based on alpha-synuclein, that would nicely satisfy the scientific narcissist in me.