It’s high time I updated you on currently – or imminently – recruiting PSP clinical trials.

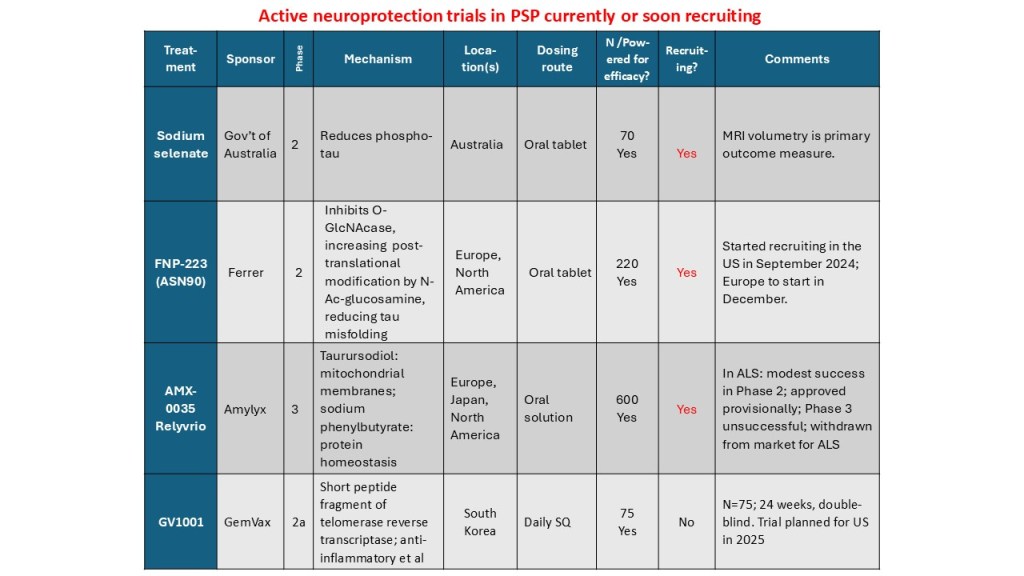

Here are the four in chronological order. All these are for “neuroprotection,” meaning slowing of the underlying disease process. They don’t attempt to improve the existing symptoms, however. That’s called “symptomatic” treatment and I’ll get around to that soon.

More details:

Sodium selenate provides supplemental selenium, which is critical for the function of 25 human enzymes with a wide range of functions. Two are relevant to PSP: glutathione peroxidase 4 and protein phosphatase 2A. The first regulates one type of programmed cell death and the second removes phosphate groups abnormally attached to the tau protein. The trial is happening only in Australia. See here for details, including contact information.

FNP-223 inhibits an enzyme called 0-GlcNAcase (pronounced “oh-GLIK-nuh-kaze”), which removes an unusual sugar molecule from its attachment to tau. The sugar is called N-acetyl-glucosamine and it prevents abnormal tau from attaching at the same spots on the tau molecule. It’s an oral tablet and the trial, which has just started, will be in both Europe and North America. Click here for details and contact info.

AMX-0035 is a mixture of two drugs in an oral solution. Both are currently marketed for conditions unrelated to neurodegeneration. The PSP trial has started in North America and will do so in Europe and probably Japan in the next few months. One of the two drugs, called sodium phenylbutyrate (marked as Buphenyl), addresses the brain cells’ management of abnormal proteins. The other, taurursodeoxycholic acid, marketed as TUDCA, helps maintain the mitochondria. Click here for details and contact info.

Finally, GV-1001 is an enzyme with anti-inflammatory action in the brain. But it’s not like a steroid or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. It acts by an mechanism that the drug company is keeping close to its chest and has something to do with DNA transcription into proteins. The drug has to be injected subcutaneously every day, like insulin. A small trial is in progress in South Korea and in you live there, here’s enrollment info. There are plans to start a trial in the US in 2025, but that could depend on the current trial’s outcome.

Soon, I’ll post something on neuroprotection trials in which the double-blind recruitment is over but the results are pending. After that will be symptomatic trials.

With all these trials in progress, CurePSP’s “Hope Matters” tagline is truer than ever.