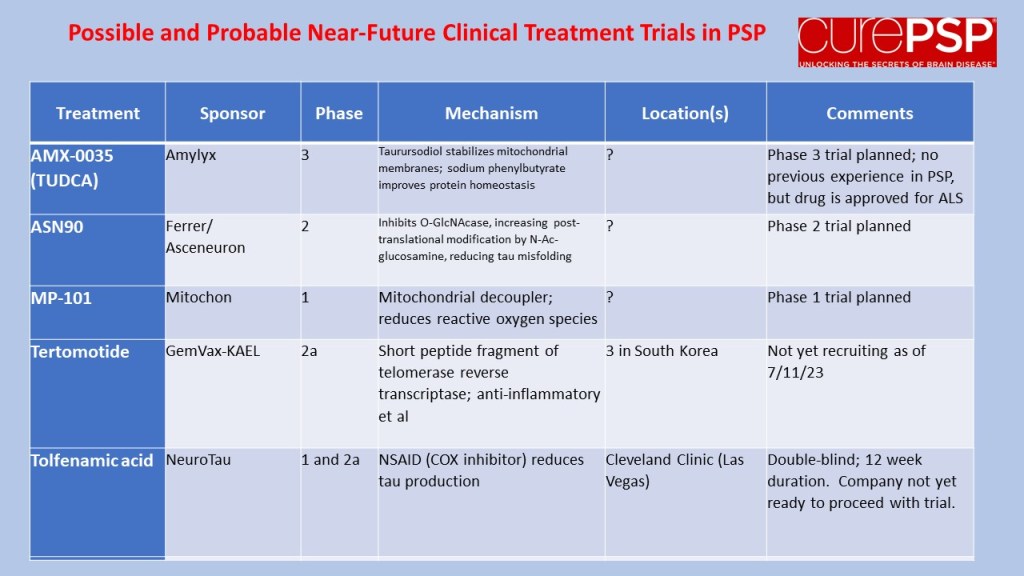

In July 2023, I posted a guardedly optimistic report on the launch of a small, Phase 2a trial in South Korea of the drug GV-1001, with the generic name “tertomotide.” Three weeks ago (sorry for my delayed vigilance on your behalf), the company released some of the results. The headline was that the drug failed to show benefit in slowing the rate of progression on the PSP Rating Scale. Nevertheless, the company, GemVax, said they remained optimistic and would proceed with plans for a Phase 3 trial in North America and elsewhere.

Here’s the deal in a bit more detail. I say “a bit” because it’s not as much detail as I’d want to see. The trial was only 6 months long and the plan was for only 25 patients in each of the three groups: higher dose, lower dose and placebo. That’s too brief and too small to demonstrate a realistic degree of slowing of progression. The best longitudinal analysis of PSP to date calculated that to demonstrate a 30% slowing in a 12-month trial would require 86 patients per group. Shorter trials and more modest slowing would require even more patients than that. But early-phase trials like this are mostly about safety, not efficacy.

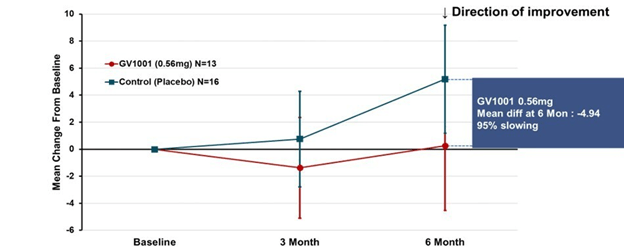

The results for the low-dose and placebo groups appears below, just for the PSP-Richardson patients:

The vertical axis is the average improvement (downward) or worsening (upward) in the total PSP Rating Scale relative to the patient’s own baseline score. (On the PSPRS, 0 is the best and 100 the worst possible score, and the average patient accepted into a drug trial has a score in the mid-30s.) At 3 months, neither group showed much change. But at 6 months, the placebo group had deteriorated by 4 points but the active drug group had remained close to its baseline. So, that looks like a benefit, but the wide standard deviation (the vertical “whiskers” at 3 and 6 months) were too large to support statistical significance (i.e., to rule out the possibility of a fluke result). Hence the negative headline, but you can see why the drug company felt encouraged by the result.

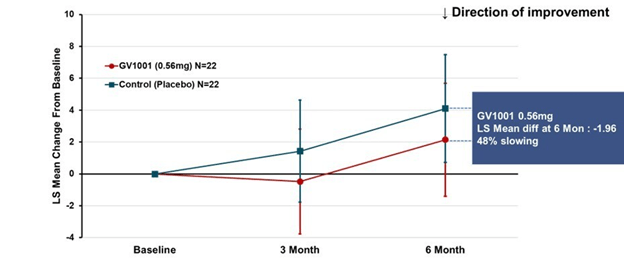

A more complicated but statistically more valid way to look at the same results appears below. This graph applies to both PSP-Richardson and PSP-Parkinson patients, hence the larger Ns:

This time the vertical axis is “least square mean change from baseline.” That uses a statistical technique called “mixed-model repeated measures” to compensate for statistical noise in the results. The basic shapes of the active drug and placebo curves look similar to the raw score graph. But now, the two lines have the same slope between 3 and 6 months, suggesting that their rates of progression over that period were the same. The interval from baseline to 3 months did have different slopes, favoring active drug. So, this could mean one of 3 things:

- There’s a neuroprotective effect (i.e., a slowing of the progression rate) that lasts only 3 months, at which point the two groups proceed to progress at the same rate;

- There’s a symptomatic improvement by the 3-month point that persists to the 6-month point, but no protective effect at any point; or

- The trial’s small size, wide standard deviations, paucity of evaluations and short duration make it impossible to draw any conclusions about symptomatic or neuroprotective efficacy.

I’ll vote for Option 3.

The data for the high-dose group, which received twice the lower dose, is not presented in the company’s press release. However, the high-dose group was included in the poster at the Neuro2024 conference (CurePSP’s annual international scientific meeting) in Toronto in October. It did not show the possible benefit that the low-dose group showed. So, that’s a little discouraging, but it’s not unheard-of in pharmacology for a higher dosage regimen to do something extra via a different chemical mechanism that counteracts some of the benefit of a lower dosage. So, that doesn’t worry me much.

Now, the issue is just how safe and tolerable the drug was. The press release only says, “The safety profile of GV1001 in the Phase 2a PSP Clinical Trial was consistent with prior safety data. GV1001 was generally well-tolerated with no serious adverse events related to the drug reported.” I’ve seen the actual numbers, and the press release is right. All of the adverse events, and there were very few, were things common in this age group or complications of PSP itself.

So, that’s probably more information than you wanted about GV-1001, or maybe it’s a lot less than you’d have liked. (I’m in the latter category.) Bottom line is that the results were good enough to justify a Phase 3 trial, which is slated to start in 2025, and that’s really good news.

Note: The text in italics explaining the two graphs and detailing the drug side effects are corrections or additions to my originally posted version. I thank Roger Moon, Chief Scientific Officer of GemVax, for supplying this information after he saw the original post. These changes do not alter my conclusions.