In response to a commenter’s question on how zebrafish became an experimental model: Zebrafish have been systematically used in research since the 1950s, starting with studies of the causes of birth defects. The original reasons for choosing that species were that it takes only four days from fertilization to hatching and that the eggs develop outside the mother’s body. The latter makes it easy to expose the developing embryos to experimental toxins by simply adding them to the water. Even after only a week post-hatching, young zebrafish half a centimeter long display most of the physiological and behavioral features of adults 6-8 times that size. Juvenile zebrafish are transparent, allowing many experimental outcomes to be easily observed without harming the animal or further interfering in its function. Besides, they’re easy to clone as a genetically uniform colony and react to toxins in ways very similar to mammals. Much of the earliest research in developing zebrafish as a genetic model was performed in the 1960s to 80s by George Streisinger, a Holocaust survivor working at the University of Oregon. Here’s a great biosketch.

Tag Archives: zebrafish

More fishy news

My post from two weeks ago, entitled, “A big little fish,” was about zebrafish as an experimental model for PSP. This creature, once the normal human tau gene has been added to its genome, is uniquely suited for efficiently screening long lists of drugs as treatment for tauopathies. I specifically cited a publication screening 147 currently available drugs modulating the attachment of phosphate groups or other regulators of tau production. It yielded two reasonable candidates for further research in other animal models or in people with PSP.

This week, there’s another important finding in zebrafish, except that it concerns not tau production, but tau disposal.

A research group at the University of Cambridge led by Drs. Ana Lopez, Angeleen Fleming and David Rubinsztein used zebrafish with the normal human tau gene to screen 1,437 compounds for use against tauopathies. All had been either FDA-approved for medical use or found in clinical trials to be safe, even if ineffective for whatever they were being tested for.

Next, they tested those 1,437 for the ability to improve the survival of a set of cells in the fishes’ eyes (the rods) that normally produce the tau protein. Of the 71 passing that test, the researchers chose the 16 that seemed easiest to study further. Of those, the most effective at rescuing cells from degenerating was the drug methocarbamol, which is available by prescription for muscle spasms under the brand name “Robaxin.” One of the several actions of methocarbamol unrelated to muscle relaxation is inhibition of an enzyme called carbonic anhydrase, which regulates the acid-base balance of cells.

Drugs that specifically inhibit carbonic anhydrase are available for use in glaucoma and in a variety of neurological disorders. Three of the most popular anhydrase inhibitors are acetazolamide (brand name Diamox), methazolamide (Neptazane) and dorzolamide (Trusopt). To determine if carbonic anhydrase inhibition explains the benefit of methocarbamol in the zebrafish, the researchers gave those three drugs to a different colony of zebrafish with a human tau gene, but in this case the human gene carried a mutation called P301L, which causes a rare, hereditary, PSP-like illness.

To the Cambridge team’s delight and ours, all three carbonic anhydrase inhibitors provided major protection against the damage caused by that tau gene mutation. A further set of experiments showed that the mechanism of protection was that the drugs work by improving the export of tau from the cells by the lysosomes. Those are organelles that perform part of our cells’ complicated garbage disposal mechanism.

I’ll let the researchers’ own words describe the overall results:

Together, our results suggest that CA [carbonic anhydrase] inhibition ultimately regulates lysosomal acidification and cellular distribution, promoting lysosomal exocytosis and tau secretion. This mechanism lowers tau levels within neurons, which, in turn, have lower levels of hyperphosphorylated and aggregated toxic tau forms, accounting for an improvement in phenotypic, neuronal loss and behavioral defects in vivo in zebrafish and mouse models. This raises the possibility of rapid repurposing of CA inhibitors for tauopathies, as our studies were performed in mice at human-like plasma concentrations. Furthermore, our data suggest that stimulation of unconventional secretion may also be a potent therapeutic approach for other neurodegenerative diseases caused by toxic, aggregate-prone intracellular proteins.

So, the “elevator explanation” is that carbonic anhydrase inhibitors make the fluid in lysosomes more acidic, enhancing their ability to load up on abnormal tau protein and dump it out of the brain cell.

This finding could lead to repurposing existing, off-patent carbonic anhydrase inhibitor drugs not only for PSP but potentially also for the many other neurodegenerative diseases that rely on the lysosomes to dispose of abnormal, misfolded proteins. Let’s hope that other animal models confirm this and that a clinical trial follows.

All the carbonic anhydrase inhibitors available are off patent, which means that their manufacturers would not be interested in investing the many millions of dollars needed to test them for a new use. But drug companies have been known to reformulate old drugs into longer-acting or better-absorbed versions, or to make inconsequential but patentable tweaks to old drugs’ chemical structure. Or maybe a deep-pocketed, non-commercial funder such as the NIH could fund a clinical trial of an existing carbonic anhydrase inhibitor.

So, that’s what should happen . . . and here’s what should not happen: For you to doctor-shop until you find one willing to prescribe a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor. For one thing, those drugs come with a long list of possible side effects and drug interactions. For another, it would be difficult to know if it’s working to slow the rate progression in you as an individual. If you go on a potentially neuroprotective drug and develop some moderate side effect, the decision to continue or discontinue the drug would depend on its benefit in you specifically, not on its effect in zebrafish or even in other people with PSP averaged together. That’s why drug trials observe each participant for a whole year and involve hundreds of participants randomized to experimental drug or placebo. We need faster and cheaper ways to do such trials and a lot of work is addressing that problem right now.

Meanwhile, don’t give up hope — or give in to the temptation of unproven, unmeasurable treatment.

A big little fish

I’ve not posted much in a while. Lots of other commitments, but unlike this blog, they had deadlines, you see. So, I have lots to catch you up on, starting with a cool study in zebrafish. This cute, 1-2-inch fishy is a popular aquarium pet. As it turns out, it also makes a great animal model for PSP.

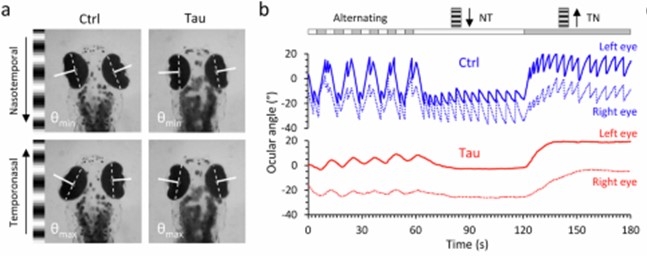

The model is created by injecting a normal human tau gene into a fertilized fish ovum. Human tau comes in six different versions, called isoforms. The tau gene used here encodes only the single isoform that accumulates in the neurofibrillary tangles of typical, non-hereditary PSP, called 0N4R tau. The resulting adult fish not only swims poorly — its eyes don’t move very well, either. It can then be bred to form an ongoing colony. Compared with mice, the leading PSP model until now, zebrafish are cheaper and easier to maintain and provide a much more efficient way to screen dozens of drugs quickly.

The figures below are from a new publication from the University of Pittsburgh led by senior author Dr. Edward A. Burton with first author Dr. Qing Bai.

Panel A shows still images from a video of a zebrafish as seen from above. The large, dark ovals are eyes and the smudge toward the bottom is the body. Panel B shows the movements of the eyes when shown a moving array of black-and-white stripes. The blue tracing is from a fish without the added human tau gene. Its eyes move crisply from one stripe to the next, but the red tracing, from a fish with the human tau gene, shows a weak response. This is identical to the response in people with PSP who are asked by a neurologist to count the stripes on a strip of cloth moved across their field of vision. It’s called “opticokinetic nystagmus” and is a good way to detect the earliest, asymptomatic involvement of the eye movements of PSP or some other disorders.

If you go to the link provided above and scroll down to the link for “Supplementary movie 1,” you’ll see a video of the eye movements and the stimulus stripes.

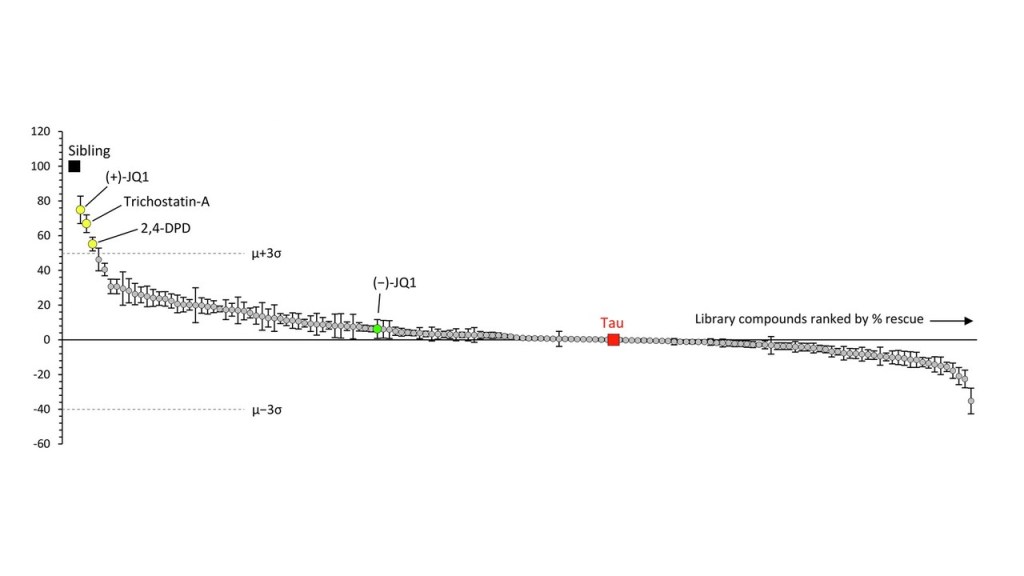

Armed with this experimental set-up and another to trace traced the fish’s spontaneous swimming in a circular dish, Drs. Bai and colleagues then screened a panel of 147 chemical compounds for any ability to correct the problems. The 147 were chosen because of their ability to modulate the attachment of small molecules to genes, one type of “epigenetic” alteration that we know occurs in PSP. Large drug screens in vertebrates are much more easily performed in zebrafish than in mice.

The graph below shows the results. Each circle is one drug and the vertical axis is the improvement or worsening it produces in the zebrafish. The “whiskers” on each circle indicate the variation among the 12 fish tested on that drug. The drugs’ results are displayed left-to-right in descending order of benefit, which means that the drugs on the right, below the “0” line, were actually deleterious. The black square labeled “sibling” indicates a littermate fish without the human tau against which the drugs’ effects are compared. The red square labeled “tau” shows another kind of comparators — the fish with human tau that were left untreated. The dotted, horizontal lines are placed at a point three standard deviations (σ) from the average (μ) of the 147 drugs’ degree of benefit (upper line) or worsening (lower line). That’s the researchers’ threshold of significant interest for the drugs.

The best-performing drug was something with the weird name, (+)-JQ1. It’s a member of a group called “bromodomain inhibitors,” which have nothing to do with the element bromine. A bromodomain is a string of 110 amino acids that forms part of many proteins involved in regulating the transcription of certain genes into their own proteins. Other inhibitors of bromodomain-containing proteins are being tested as treatment for various cancers. My clinicaltrial.gov search on “bromodomain inhibitor” produced 52 such trials, though none so far for (+)-JQ1 itself. The second-best bromotomain inhibitor emerging from the zebrafish screen is trichostatin-A, a non-FDA-approved, anti-fungal antibiotic with potential anti-cancer properties and 137 listings in clinicaltrials.gov. Third is 2,4-OPD, on which I found no information anywhere.

Bonus fact for the real science nerds: The graph shows a green data point for (-)-JQ1. That’s the “enantiomer” of (+)-JQ1. Enantiomers are pairs of molecules with identical sets of atoms in mirror-image configurations. Some such pairs have identical properties but many don’t. A good example of the latter is levodopa, the (-) version of dihydroxyphenylalanine. It helps Parkinson’s dramatically and PSP modestly, but the (+) version, which would be called “dextrodopa,” does neither. The “dextro-” and “levo-” prefixes refer to the clockwise or counterclockwise rotation that a solution of the compound imparts to the plane of polarized light.

So, let’s await experiments of (+)-JQ1 and trichostatin-A in other models such as tau knock-in mice, stem cells and organoids. Let’s also await screens of other classes of drugs in the cute little zebrafish that provide a great new, efficient test bed for PSP treatments.