Here’s the first of two installments summarizing the original, PSP-related research presentations at the annual conference of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society held in early October 2025 in Honolulu.

The listing is in no particular order and each is followed by my own editorial opinion. I’ve culled the 29 PSP-related presentations down to the twelve I considered most interesting considering both their scientific importance and their potential interest to this blog’s readers.

—

Clinical Deficits, Quality of Life and Caregiver Burden across PSP Phenotypes

A. Cámara, I. Zaro, C. Painous, Y. Compta (Barcelona, Spain)

Caregiver burden is greater for PSP-Richardson syndrome than for other PSP subtypes, and quality of life showed a statistically non-significant trend for PSP-RS as well. This information may be useful in counseling patients and caregivers.

LG comment: This result would be expected given the rapid progression of PSP-RS and its high prevalence of falls and dementia relative to most other PSP subtypes. The study importantly points out that caregiver burden receives too little attention from clinicians, researchers, policy planners and insurors.

Clinical Features Suggestive of Alpha-Synucleinopathy in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

C. Painous, A. Martínez-Reyes, J. Santamaria, M. Fernández, A. Cámara, Y. Compta (Barcelona, Spain)

Rapid eye movement behavioral disorder and reduced ability to smell are known to be very common in Parkinson’s disease and other alpha-synuclein-aggregating disorders but also occur to some extent in those with PSP. All of this study’s patients with PD and 10% if those with clinically typical PSP had a positive spinal fluid alpha-synuclein seeding amplification assay (SAA).

LG comment: The new SAA test is not perfectly specific for synucleinopathies and could produce a false positives in people with PSP. The same is true for RBD and reduced smell sensitivity.

Identification of Genetic Variants in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy in China

Y. Kang, W. Luo (Hangzhou, China)

Pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants consistent with their respective inheritance patterns were detected in 20% (8/40) of patients: three carried PSP-related variants (CCNF, DCTN1, POLG), while five harbored variants in neurodegeneration genes linked to PSP-like phenotypes (AARS1, TDP1, FA2H, TBP, ATXN8). The controls were only historical controls from the literature.

LG comment: This list of genetic variants, each conferring a very slight increased PSP risk, differs from the lists reported in Western populations, which also have important differences from one another. The differences could be related to geographically or culturally related environmental contributions (which need different genetic backgrounds to cause damage) or to differences in laboratory methods or choice of non-PSP control populations.

Unraveling the Genetic Architecture of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy in East Asians

P. Chen, R. Lin, N. Lee, J. Hsu, C. Tai, R. Wu, H. Chiang, Y. Wu, C. Lu, H. Chang, T. Lee, Y. Chang, C. Lin (Taipei, Taiwan)

Using a Taiwanese population, this study identified three likely pathogenic variants, in the genes called APP and ABCA7, and the mitochondrial genome. It also found 39 variants of unknown significance in 37 PSP patients (20.9%), involving other genes, many of which were already known to confer slight risk for PSP.

LG comment: The difference in apparent genetic risk factors between Shanghai (previous abstract by Kang et al) and Taiwan underscores the possibility of differences in methodology, although ethnic differences between those two geographical areas could be contributing. Genetic study of PSP in East Asians could benefit all ethnicities by identifying previously unsuspected cellular pathways involved in the disease.

Multimodal imaging Integrating 18F-APN-1607 and 18F-FP-DTBZ PET in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

C. Dong, J. Ma, S. Liu (Beijing, China)

Several kinds of positron emission tomography (PET) imaging are being tested for their ability to accurately diagnose PSP. Two of them were applied concurrently to a group of 20 participants with PSP and a control group. One, called 18F-APN-1607, shows abnormal accumulation of the tau protein and the other, called 18F-FP-DTBZ, images the neurons that use dopamine. The result was that 16 of the 20 were correctly identified by the 18F-APN-1607 and three of the other four were identified by the 18F-FP-DTBZ as being probable Parkinson’s disease. The conclusion is that performing both types of PET could provide more accuracy than the tau PET alone in distinguishing PSP from PD.

LG comment: This result is consistent with the age-old medical principle that there’s no such thing as a perfectly accurate diagnostic test. Two or more tests measuring different aspects of the same disease can work in a complementary manner to improve diagnostic accuracy. Fortunately, PET is a nearly harmless, nearly painless test. Its main drawbacks are time, expense and insufficient availability of many kinds of PET outside of referral centers.

Levodopa response in pathology-confirmed Parkinson’s Disease, Multiple System Atrophy and Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

V. Arca, J. Jurkeviciene, S. Wrigley, P. Cullinane, J. Parmera, Z. Jaunmuktane, T. Warner, E. de Pablo-Fernandez (London, United Kingdom)

About one in three people with PSP experiences some degree of benefit on levodopa, a statistic that prompts most neurologists to give that drug a try. However, the benefit is often short-lived. To measure this in a formal way, these researchers reviewed the medical records of autopsy-confirmed patients with PSP, PD or MSA. Those responding well for over two years were 2% of those with PSP, 86% of those with PD and 8% of those with MSA.

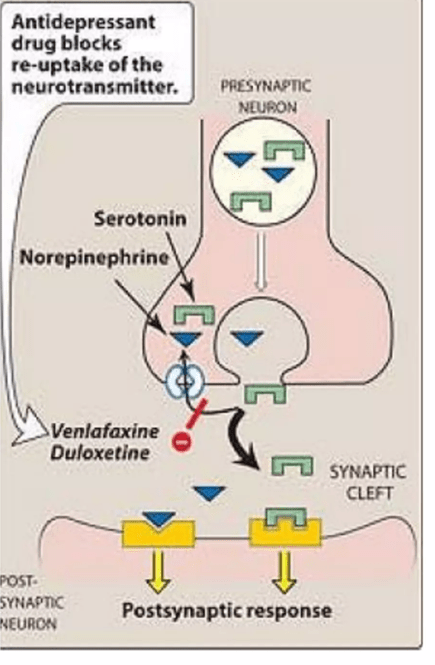

LG comment: The short duration of useful benefit from levodopa in PSP means that each patient enjoying a benefit after the drug initiation should be re-evaluated at each subsequent visit for a continued benefit. As levodopa can have long-term side effects such as low blood pressure, hallucinations and involuntary movements, a dosage taper carefully monitored by the physician should be considered after the first year or so of treatment.