We saw some real progress against PSP in 2025. This post and the next list my top 10 developments from the past year in approximate and very subjective descending order of importance:

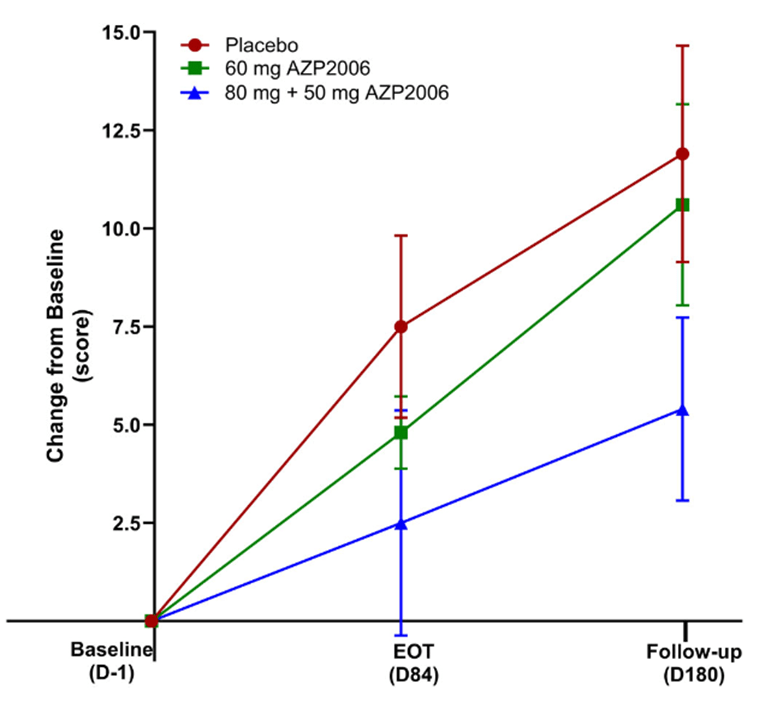

- AZP-2006, a drug that enhances the breakdown of abnormal tau protein by the cells’ lysosomes, was found to slow the progression of PSP by 64%. The catch is that even that impressive-sounding result did not reach statistical significance because the trial was too small, having been designed mainly to assess safety. Furthermore, its design did not exclude the possibility of random bias in the selection of the participants. But the sponsor company plans to start a much larger and better trial in the second quarter of 2026 as part of the PSP Trial Platform. My blog post on that is here.

- A new subtype of PSP has been identified and named PSP-PF. It was formed from chunks of two of the previously known ten subtypes, PSP-frontal and PSP-postural instability. If confirmed by other researchers, it will probably be the third-most common subtype, and the second-most rapidly progressive. The discovery could allow the expansion of drug treatment trials, which prefer to enroll rapidly-progressing participants, to include a more people with PSP than just the ~half with PSP-Richardson syndrome. My blog post is here.

- The PSP Trial Platform announced that it will start testing a PSP vaccine called AADvac1 in the second quarter of 2026. Unlike the passively administered anti-tau antibodies that failed a few years ago, this is an active vaccine, meaning that it stimulates the immune system to make its own antibodies. As my May 2025 blog post point out, AADvac1 has given encouraging early results against one large sub-group of people with Alzheimer’s disease.

- CurePSP announced its new Biomarker Accelerator Program, offering grants of up to $500,000 for major projects to identify and characterize diagnostic tests for PSP. The program will consider applications involving not only markers to distinguish PSP from other disorders, but also those predicting an individual’s course and to assess change in the disease to use as outcome measures in treatment trials and other research.

- Neurofilament light chain, a protein released into the spinal fluid and blood by many kinds of damage to brain cells, accumulated more evidence of its potential as a diagnostic marker of PSP. Although NfL is the most promising fluid marker for PSP, it’s not quite ready for routine use because of as yet insufficient sensitivity, specificity and consistency across different labs. Another major outstanding issue is to what extent blood can replace spinal fluid as a test medium. However, with the publication of each small advance, more research groups and funders become interested.

My next post will cover developments 6-10.