A common diagnostic problem is distinguishing PSP from normal-pressure hydrocephalus (NPH), but a new way to look at brain MRIs using artificial intelligence could have the solution. I’ll now administer the usual large dose of background information:

NPH occurs in the same age group as PSP but is much more common. Its three classic features sound a lot like PSP: frontal cognitive loss, urinary incontinence, and gait impairment. But those often don’t appear until late in the course and other issues such as general slowness, reduced vertical eye movement and tremor can precede them. Of course, those also are shared with PSP.

In NPH, the fluid-filled cavities of the brain enlarge and over-stretch the brain’s fibers to produce the symptoms. The cause of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) accumulation in many cases is a partial blockage of its normal absorption into the blood. In some cases, that appears to be the result of scarring from an old episode of brain infection or bleeding around the brain. Other cases, called “idiopathic NPH,” have no history of such inflammatory events and their cause remains unknown. There is also in NPH some evidence of a neurodegenerative component, as in PSP, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s.

A diagnosis of NPH depends less on the clinical history and exam than on two other things: 1) a specific pattern on MRI of brain tissue loss and enlarged CSF spaces and 2) benefit after removal of some CSF. I’ll discuss those in turn:

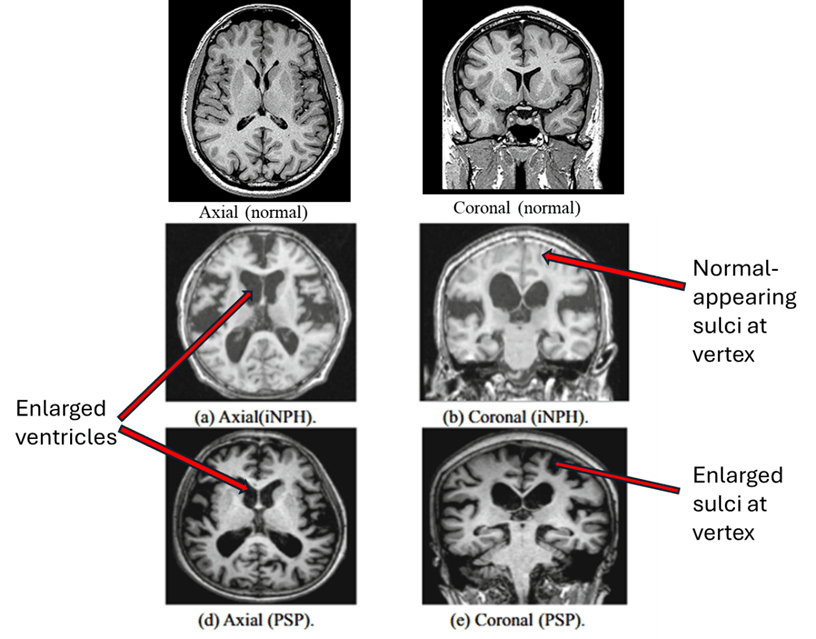

A. MRI diagnosis. Below are MRI images from idiopathic NPH (middle row) and PSP (bottom row). The main differences between PSP and NPH are indicated by the labels on the right. PSP features widening of the spaces between the brain’s folds caused by atrophy of the brain tissue. But in NPH, the spaces toward the top of the brain are as tight as, or tighter than, normal. There are other, less reliable, MRI differences, none of them adequately sensitive or specific for NPH.

B. CSF diagnosis. The other diagnostic feature is the response to CSF drainage. It’s not just a diagnostic test; it also predicts the likely response to treatment by shunting. If someone in whom NPH is suspected has an MRI consistent with NPH and no signs of other potential causes of their symptoms, the physician will usually perform a spinal tap to remove about 30-50 ml with before-and-after videos of the gait and other actions. (The average adult has about 100-150 ml at any one time, but the daily turnover is about 500 cc, so the 30-50 ml loss is replaced after only a few hours.) Some neurologists prefer the greater diagnostic reliability provided by a more prolonged period of drainage via a soft plastic tube temporarily inserted into the lumbar CSF space (the same place where the needle of a spinal tap goes), but this can have complications.

Whichever temporary method of CSF removal is used, a good symptomatic response would prompt consideration of a tube, called a “shunt,” permanently implanted into the brain to direct flow of some CSF, usually into the abdominal cavity. Of course, implanting such a shunt into the brain can produce complications such as infection or bleeding, so we’d first like to make sure the person doesn’t have PSP, which offers no potential shunt benefit to compensate for that risk.

I should point out that PSP is far from the only disease that can mimic NPH and not respond to shunting. Among the others are the far more common PD and AD. That means that only a small minority of “NPH candidates” actually has NPH, so placing brain shunts in all the candidates would be highly inadvisable, to put it mildly. So, it’s important to make the right diagnosis.

Over the decades since 1965, when NPH was first described in the literature, the number of proposed diagnostic methods has been prodigious and none has been sufficiently accurate. But now, the cavalry may have arrived in the form of AI. A group of researchers led by Drs. Fubuki Sawa and Syoji Kobashi of the University of Hyongo in Japan has used “convolutional neural networks,” a form of deep learning, to produce a predictive model. It used the most specific and informative MRI features from 59 people with NPH who subsequently benefitted from shunting and 65 people with PSP by current, validated criteria. The resulting statistical formula produced a perfect score of 1.000 in the area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC). (Wikipedia has a nice little explanation of that statistic here. Basically, it’s the ability of a diagnostic test to minimize both false positives and false negatives, with 1.0 being perfect and 0.5 being equivalent to a coin toss. Its virtue is that it’s applied to an individual, not merely to the averages of two groups.)

Perhaps easier to intuit is the test’s accuracy, according to Sawa et al, of 0.983. That statistic is formally defined as the fraction of all the participants who received a correct diagnosis from the formula. Such power for a diagnostic test is nearly unheard-of in medicine, but keep in mind that the definition of NPH in this study wasn’t autopsy, but an MRI showing the typical features plus a response to CSF shunting. So that means that the input and outcome variables were partly redundant, inflating the accuracy to some extent.

The other caveat is that this technique only distinguished PSP from NPH, not from PD or anything else. But the general AI-based statistical technique should be applicable to many kinds of diagnostic situations where the two candidate diseases cause atrophy in different parts of the brain. We eagerly await those papers from Drs. Sawa and Kobashi, and we hope, others.

The take-home if you’re someone with PSP:

- Should people with a diagnosis of PSP get a new MRI each year in the hope that a pattern of NPH will emerge and a shunt procedure confer improvement? Probably not, because an MRI showing the abnormalities of PSP won’t change into the abnormalities of NPH over time.

- Should people with PSP get a shunting procedure just in case they actually have NPH? Definitely not, as the risk of both short- and long-term shunt complications far exceeds the likelihood of benefit.

- Instead of either of these: Keep hydrated and well-nourished, avoid falls and aspiration, minimize unnecessary medications with your doctor’s advice and consent, get some exercise, maintain a social life, and join an FDA-approved clinical trial if one is available.

- Also, consider getting a second diagnostic opinion from a neurologist subspecializing in movement disorders, who can scrutinize the original MRI for evidence of NPH that might have eluded the original neurologist or radiologist.

The take-home if you’re a neurologist:

At each follow-up visit or phone call, keep in mind the possibility that the diagnosis may not actually be PSP, but something much more treatable — like NPH. Then, work up or refer accordingly.