Here’s the second of two installments summarizing the original, PSP-related research presentations at the annual conference of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society held in early October 2025 in Honolulu. I posted the first installment yesterday.

The listing is in no particular order and each entry is followed by my own editorial opinion. I’ve culled the published 29 PSP-related presentations down to the twelve I considered most interesting considering both their scientific importance and their potential interest to this blog’s readers.

—

Oxidative Stress in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

P. Alster, D. Otto-ślusarczyk, M. Struga, N. Madetko-Alster (Warsaw, Poland)

The authors measured the concentration of a marker of oxidative stress called “thiobarbituric acid reactive substances” (TBARS) in the blood of 12 people with PSP-Richardson syndrome, 12 with PSP-Parkinson, and 12 healthy controls. Although oxidative stress is known to be part of the PSP process in the brain, there has been no attempt to compare PSP subtypes in this regard. The result was that compared to controls,TBARS levels were high in PSP-P but not in PSP-RS.

LG comment: Blood tests for TBARS and perhaps other measures of oxidative stress could become a way to distinguish PSP-P from PSP-RS for purposes of clinical trial enrollment. If further research supports the finding, potential treatments that reduce oxidative stress would become less attractive for PSP-RS and more attractive for PSP-P.

Disease Characteristics of the First 100 Participants in the CurePSP Genetics Program Cohort

C. Obasi, V. Zhao, C. Martinez, S. Scholz, H. Morris, N. McFarland, M. Nance, J. Wang, N. Mencacci, B. Cuoto, T. Foroud, J. Verbrugge, A. Miller, L. Heathers, L. Honig, A. Lang, F. Rodriguez-Porcel, P. Moretti, M. Mesaros, J. Brummet, K. Diaz, A. Wills (Boston, USA)

The CurePSP Genetics Program is designed to enroll large numbers of people with PSP, CBS and MSA and to use their DNA samples to find genetic causative factors not discovered by previous, smaller studies. After the first 10 months, 74 volunteers with PSP have enrolled, 8% percent of whom claim to have a living or deceased relative with PSP.

LG comment: The authors caution that this project’s stated objective of finding genetic causes of PSP could over-sample people with a positive family history. On the other hand, some relatives with subtle PSP may have died (without an autopsy) from something else before receiving a correct diagnosis. So, that 8% could be an under- or an over-estimate. Enrollment will continue through the end of 2028 and the full genetic analysis should appear in 2029.

Multiscale Entropy: a New Oculomotor Measure of PSP.

C. O’Keeffe, A. Gallagher, J. Inocentes, B. Coe, B. White, D. Brien, D. Munoz, R. Walsh, T. Lynch, C. Fearon (Dublin, Ireland)

The eye movements of PSP are famously reduced in amplitude, but they are also abnormally irregular and complex in a way not evident on a standard neurological examination. This study used a piece of hardware called “Eyelink 1000+” to measure irregularity (which they call “entropy”) of eye movements during 40 seconds’ viewing of photos of scenery and faces in 24 participants with PSP, 38 with Parkinson’s, and 9 controls. The result was that the irregularity of vertical (up and down) movement in PSP significantly exceeded that in PD and in controls. Importantly, the degree of eye movement irregularity did not correlate with the overall PSP Rating Scale, suggesting that detectable irregularity could exist even at very low PSPRS scores, at a point in the disease course before a clear diagnosis is possible. The authors suggest that this test could become an inexpensive, non-invasive diagnostic test for PSP valid at even the earliest phase of the illness.

LG comment: Undoubtedly, larger studies will allow calculation of reliable diagnostic statistics such as the “area under the receiver operating characteristic curve” for this test. Equally undoubtedly, the result will be less than perfect. But perhaps this can be combined with other measures of eye movement at the same testing session to provide a combined “PSP eye movement index” with close to 100% sensitivity and specificity.

Spatial Metabolic Covariance Networks in PSP: Implications for Symptomatology and their Neural Basis

B. Wang, W. Luo (Hangzhou, China)

Spatial independent component analysis (ICA) is a statistical technique for finding patterns in images. This project analyzed FDG PET scans, a map of energy production in the brain, to characterize specific networks of interacting areas that go wrong in PSP. They compared 85 participants with PSP with 70 healthy controls, finding three areas with energy production correlated with aspects of PSP disability. They are a) the dorsomedial thalamus-medial prefrontal cortex (dmT-mPFC) network, causing gait and balance loss; b) the posterior cingulate cortex-lateral prefrontal cortex (PCC-LPFC) network, causing cognitive loss, stiffness and slowness; and c) the putaminal network, causing overall motor control loss.

LG comments: Understanding which sets of brain cells are affected worst in PSP could allow intelligent targeting of future treatment techniques such as deep-brain stimulation and transcranial (i.e., through the intact scalp and skull) magnetic or electrical stimulation.

Validation of the Short Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Quality of Life Scale in PSPNI

Q. Shen, XY. Li, J. Wang, FT. Liu (Shanghai, China)

The PSP Neuroimaging Initiative (PSPNI) is a large, long-term, observational study based in Shanghai, China that investigates far more than just imaging. Since the 2024 publication by a German group of a short, easy version of the PSP Quality of Life Scale (PSP-ShoQoL), the PSPNI has been investigating its properties. They now report that the information value of this 12-item scale is similar to that of the original, 46-item version, and its sensitivity to change over a year’s time was good.

LG comment: The FDA has made it clear that a new drug’s ability to improve patients’ quality of life is an important consideration in their approval decisions. While a more global scale featuring objective neurological findings (such as the PSP Rating Scale or its abridged versions) will continue to serve as the “primary” outcome measure in PSP neuroprotection trials, I expect the new PSP-ShoQoL will soon become first among the “secondary” outcome measures. (The FDA may base an approval decision on the secondary outcome measures if the result on the primary is good but not dramatic. Similarly, it could approve a drug with multiple favorable secondary measures even if the primary result is borderline.)

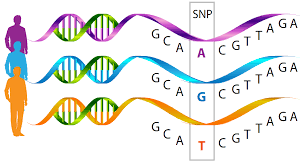

Plasma Tau-Species-Containing Neuron-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as Potential Biomarkers for Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

YC. Zheng, HH. Cai, WY. Kou, ZW. Yu, T. Feng (Beijing, China)

Neuron-derived extracellular vesicles (NDEVs) are tiny pieces of brain cells that break away and may enter the spinal fluid or bloodstream. As tiny, encapsulated “samples” of the parent cell’s contents, NDEVs have been investigated as a sensitive way to measure the molecular contents of those cells. This project measured concentrations of tau, 4-repeat tau (the kind of tau in the tau tangles of PSP), and tau with an abnormal phosphate at amino acid number 181 (ptau181) in NDEVs in the blood. The statistical model incorporating these biomarkers yielded an AUC of 95% for distinguishing PSP patients from healthy controls, with a sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 85%, and an AUC of 95% for distinguishing PSP from PD. (The AUC, or area under the receiver operating curve, is a measure of the ability of a single person’s measurement to determine the presence or absence of the corresponding disorder. An AUC of 100% is perfect, 50% is no better than a coin toss, and over 85% is considered good enough for most purposes.)

LG comment: These AUCs in the mid-to-high 90s are superb, but so far, assays of NDEVs are technically tricky and not ready for the prime time of regular clinical care. But I predict that commercial availability will follow soon after other labs confirm this impressive result and extend it to distinguishing PSP not just from PD and controls, but also from CBD, FTD, Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies.