Happy New Year, all!

Yesterday’s post was the first five of my top ten PSP news items of 2025. Here are the rest, again in approximate and subjective descending order of importance.

- New ways of interpreting standard MRI images have gained ground as diagnostic markers for PSP. One is a test of iron content in brain cells called “quantitative susceptibility mapping” (QSM). Nine papers on that topic appeared in 2025, four in 2024 and none previously. It’s looking like combining QSM data from ordinary measurements of atrophy of PSP-related brain regions could be the ticket, as both measures come from the same test procedure, unpleasant though it may be, and they measure different things.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of PSP’s type of tau (“4-repeat tau”) has made advances in 2025. This test requires intravenous injection of a “tracer” with a radioactive component that enters the brain tissue,sticks to the target molecule and is then imaged. It can distinguish PSP from non-PSP, distinguish among various PSP subtypes, and quantify the disease progression. The leading such tracer in terms of readiness for submission to the FDA is [18F]PI2620 and a distant second is [18F]APN-1607 ([18F]-PM-PBB3; Florzolotau). A tau PET tracer called Flortaucipir is on the market as a test for Alzheimer’s disease, but it performs poorly for PSP.

- There’s brain inflammation in PSP, but it’s not clear whether it’s a cause or a result of the loss of brain cells, or both. Regardless, measuring the quantity and type of inflammation using blood or PET could shed light on the cause of the disease, identify new drug targets, and serve as a diagnostic marker. A good example of 2025 research on blood markers of inflammation in PSP is here and on PET imaging of inflammation is here .

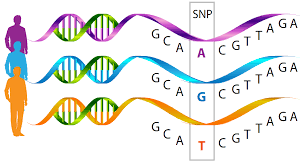

- We know of variants in 21 different genes, and counting, each of which subtly influences the risk of developing PSP or its age of onset. The area of the genome most important to PSP is the one that includes the gene encoding tau (called “MAPT”) on chromosome 17. The most important PSP genetic advance in 2025 was probably the discovery that some PSP risk is conferred by extra copies of a stretch of DNA, not the sequence itself. This news could inspire investigation of other places in the genome for other copy-number variants, which are much trickier to find than sequence variants. Here’s a great review of the latest in PSP genetics.

- And lastly, a disappointment: a negative result of a double-blind trial of the combination of two drugs already approved for other conditions: sodium phenylbutyrate (“Buphenyl”) and taurursodeoxycholic acid (“TUDCA”). Blog post here. Sponsor’s press release here. Buphenyl protects the endoplasmic reticulum, which helps manufacture proteins, and TUDCA helps prevent brain cells from undergoing self-destruction (“apoptosis”) in response to various kinds of stressors. The pair were theorized to act synergistically. The trial’s upside is that its placebo group data can be used to provide better statistical support for future innovations in clinical trial design.