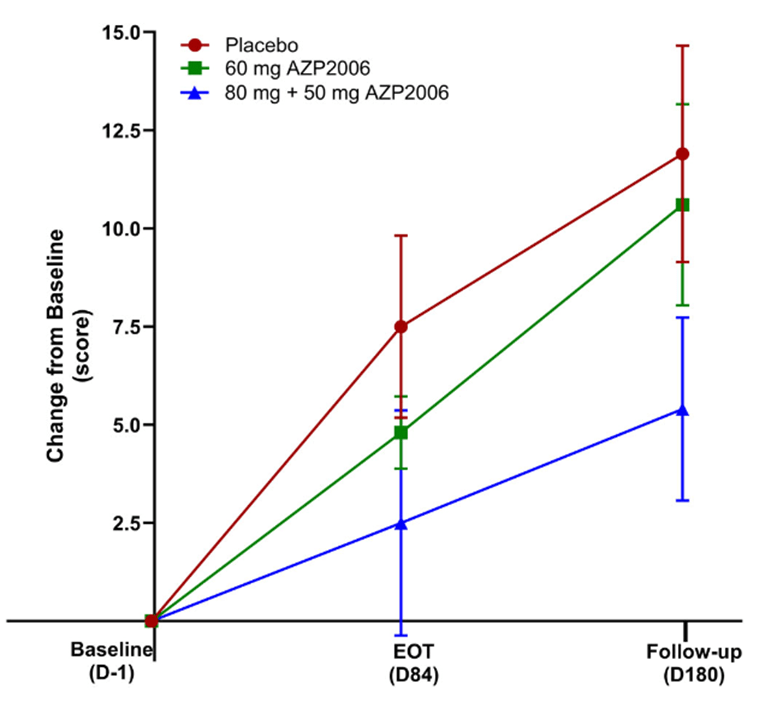

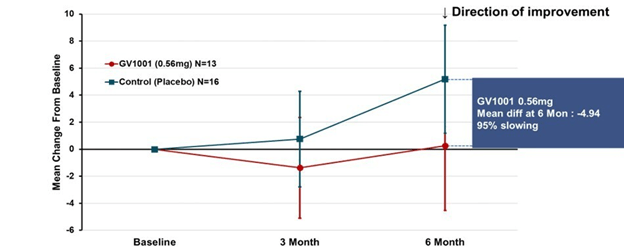

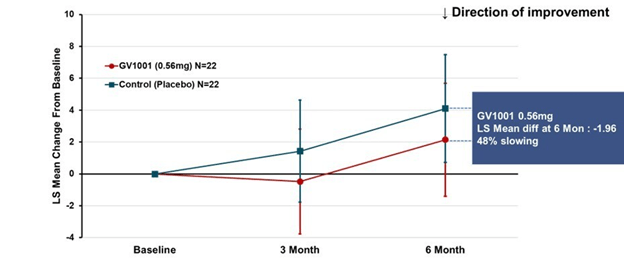

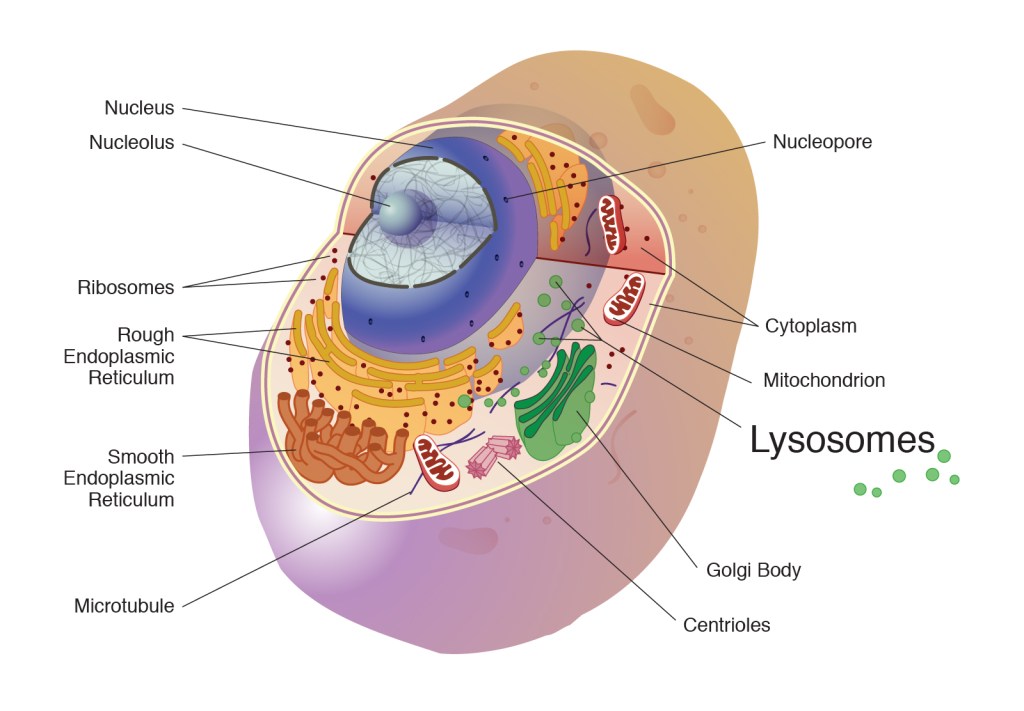

Some good news for those seeking to enroll in a PSP drug trial: The PSP Platform (PTP) is scheduled to start enrolling in the first quarter of 2026. The first two drugs will be the AADvac1 and AZP-2006. The first is a vaccine that stimulates the immune system to make its own anti-tau antibodies. The second boosts the part of the brain’s garbage disposal system most relevant to PSP.

The third drug is still being finalized with its Pharma sponsor and some points in the study protocol await approval by the FDA. Only then could the results potentially be used to support a new drug application. These delays explain the start-up postponement from December 1, 2025 listed in ClinicalTrials.gov to early 2026.

As described in more detail in previous posts here and here, the PTP is a group of about 50 centers in the US led by neurologists at UCSF, UCSD and Harvard. They have created an infrastructure to test up to three drugs simultaneously, each in its own set of 110 participants. A major advantage of such a plan is that all three trial groups share the same placebo group. That way, each participant has only a 25% chance of being assigned to placebo. The other obvious advantage is cost savings, which could lower the bar for a company to give its drug a go. The trial is heavily subsidized by a grant from the NIH budgeted for about $14.5 million this year and similar amounts annually through 2029. https://reporter.nih.gov/project-details/11160498

The names and locations of the approximately 50 participating sites across the US have not been announced, but those interested should keep an eye on the ClinicalTrials.gov page https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT07173803 or wait a few days and contact the study’s central enrollment center at 213-821-0569 or psp-participate@usc.edu at the University of Southern California. But perhaps the best option is simply to register with CurePSP for updates on the trial’s status.

Reality check: As for most PSP drug trials, the hope is to slow the rate of progression. The PTP is designed to be able to detect a slowing relative to the placebo group of 33% or better over the 12-month period of the trial. The trial’s design is based on assumption that the drug would not improve the symptoms – it would at best slow down the pace at which they worsen. But if all goes well, that could mean many months or even a couple of years of good-quality life. An even better outcome to hope for is that one of the drugs would work well enough to prevent progression altogether (“100% slowing”), maintaining the present level of symptoms for the remainder of whatever would have been the person’s lifespan without PSP.

A 33% slowing is a very realistic hope. That 100%-slowing scenario is only a distant hope, but one that’s theoretically possible. And hope does matter.