I’ve been thinking about PSP subtypes a lot lately, mostly because of last week’s report of an eleventh subtype, PSP-PF, comprising elements of the PSP-PI and PSP-F types. See my recent post for more explanation. I’ve read what I can about what causes the various subtypes to prefer slightly different parts of the brain. The general thought on that right now is “tau strains.”

Think of tau as a species, like the dog, and its strains as breeds. Let’s not get into the molecular nature of the inter-strain differences or what produces them. Instead, let’s recognize that those strains could theoretically underlie the differences among the 11 PSP subtypes by introducing differences in predilections for different groups of brain cells sharing a location or function. But this week, another possibility emerged as an explanation of the subtypes’ brain-area preferences: abnormal venous circulation.

The study in Parkinsonism and Related Disorders performed brain MRIs and routine clinical office exams on 95 people with PSP. Of those, 64 had one of the three “cortical” subtypes (PSP-speech/language, PSP-corticobasal syndrome, and PSP-frontal). The other 31 had one of the “subcortical” subtypes (PSP-Parkinsonism, PSP-progressive gait freezing, PSP-postural instability). There were also 50 healthy participants as controls.

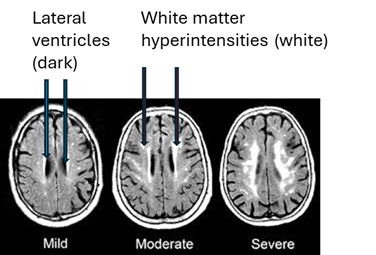

The three groups of participants were compared with regard to the size, number and location of any “white matter hyperintensities” (WMHs), examples of which appear in the MRIs below as the irregular white dots and splotches. In mild form, they’re common in healthy, older people and more so in those with high blood pressure, diabetes and other vascular risk factors. You can see how some of them sit smack up against the black slits in the middle of the brain, the spinal-fluid-filled lateral ventricles, and some are much closer to the outer, convoluted surfaces of the brain, the cerebral cortex. (Image from Inzitari D, Pracucci G, Poggesi, et al. BMJ. 2009 Jul 6;339:b2477. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2477

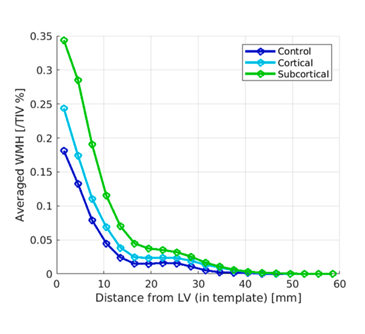

The graph below shows the current paper’s main results: (from Fu M-H, Satoh R, Ali F, et al. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders. 2025 Dec 22:143:108170. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2025.108170).

This graph’s vertical axis is a measure of the WMHs’ total volume, expressed as a percentage of total intracranial volume. The horizontal axis is the WMHs’ location expressed as average distance from the lateral ventricle. The participants with the subcortical subtypes of PSP had the greatest volume of WMHs and their average distance from the lateral ventricles was greatest. The people with the cortical subtypes ranked lower in both measures, and the control participants ranked lowest. However, after correcting for various potential confounders, the differences remained statistically significant only for the areas between 12 and 30 mm from the lateral ventricles.

How to interpret this? Let’s start with some background:

- The tiny veins draining blood from the brain are divided into deep and superficial systems. Each flows into its own set of larger veins en route to the heart.

- WMHs are areas of scarring. They’re largely of unknown cause, but they correlate with risk factors for stroke, which is mostly related to narrowing of arteries, not veins.

- Multiple sclerosis, which produces areas of white matter inflammation and scarring more severe than those of PSP, has been linked to insufficiency of venous drainage of the brain.

- Normal-pressure hydrocephalus, which is similar in many ways to PSP and even can have PSP-like changes in the brain cells, has been shown (by the same research group as the present paper) to include insufficiency in one of the deep veins.

The areas of brain yielding the graph’s statistically significant results drain into the deep venous system. They’re unrelated to brain territories supplied by any specific arteries. The authors tentatively conclude that the WMHs may be caused by insufficiency in the brain’s deep venous system. They are appropriately cautious about assigning cause-and-effect, but the obvious question raised by their results is whether narrowing of the deep veins, and not any differences in tau or its post-translational modifications, could explain some, or maybe all, of the variety of PSP subtypes.

—

The authors of this paper overlap with those of last week’s about the new PSP-PF subtype summarized in my last post. All from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester or Jacksonville, they include first author Dr. Mu-Hui Fu working under senior author Dr. Jennifer Whitwell, a veteran leader in PSP-related imaging research.