I hope you will forgive my 24-day posting hiatus. To make it up to you, I bring good news: The trial of AMX-0035 in PSP is planning to expand its enrollment activities in the next few weeks, and this drug’s track record is unusually encouraging.

The trial, dubbed “ORION” for some reason, initiated enrollment over the past two months at eight sites in California, Florida, Massachusetts, Michigan, Tennessee and Texas. 32 other sites in the US and dozens in Europe and Japan will open in coming months, with a total enrollment target of 600 patients. Those interested can email clinicaltrials@amylyx.com, check clinicaltrials.gov or the company’s own site. The trial will include a 12-month double-blind period with a 40% chance of assignment to the placebo group, followed by a 12-month open-label period. Trials like this usually take about a year or two to fully enroll, another year for the last enrolled participant to complete the double-blind and another few months to analyze the data.

The drug company is Amylyx Pharmaceuticals, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. They held a meeting a few days ago for their US sites’ neurologists and coordinators, where I gave a detailed lesson on proper administration of the PSP Rating Scale, which will be the study’s main outcome measure. (Disclosure: Amylyx paid me for that presentation and for general advice on the trial’s design but I have no financial interest in the success of the company or the drug.)

The treatment in question is actually two drugs, taurursodiol and sodium phenylbutyrate, both administered orally as a powder stirred into water. The first addresses the dysfunction of the mitochondria in PSP. The second reduces stress in the endoplasmic reticulum and enhances the unfolded protein response, both of which are also dysfunctional in PSP. All of these cellular functions are related and lab experiments show that the two drugs combined work better than the sum of their individual effects.

Unlike any of the other new drugs currently or or soon to be tested for PSP, AMX-0035 has been found to help a related disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gehrig disease), where it appears to slow the progression by about 25% and prolongs survival accordingly. The drug, branded “Relyvrio,” won approval from the FDA for ALS last year and is gaining widespread acceptance among neurologists in treating that condition.

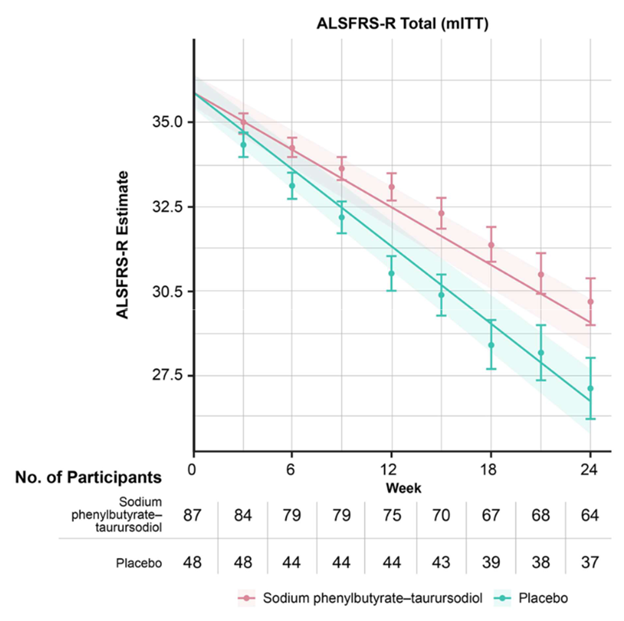

The graph below (from Paganoni et al, New England Journal of Medicine, 2020) shows the worsening of the main ALS disability measure (vertical axis; note that the bottom is not zero) over the 24 weeks of the trial (horizontal axis). The orange line/shaded areas and the means/standard error bars represent the patients on AMX-0035 using two different statistical techniques. The patients on placebo are shown in green.

The graph below (also from Paganoni et al), called a Kaplan-Meier survival plot, shows the fraction of patients in the ALS trial remaining alive without tracheostomy or hospitalization (vertical axis) along the 24 weeks of the trial (horizontal axis).

This is great for people with ALS, but that’s not a tau-based disorder like PSP. However, in a Phase 2 trial in Alzheimer’s disease, which is partly a tau disorder, AMX-0035 did reduce spinal fluid levels of both total tau and of a toxic form called p-tau 181. That trial was too small and brief to reveal any efficacy of AMX-0035 to slow or halt AD progression but I assume a proper Phase 3 trial will follow.

Side effects of AMX-0035 in the AD trial have not been published, but in the ALS trial, nausea, diarrhea, excess salivation, fatigue and dizziness occurred in 10% to 21% of patients on the drug and in slightly lesser percentages of those on placebo.

If AMX-0035 shows the same result in PSP as it did in ALS, that means about one additional year of survival for the average patient, and even more if the disease can be diagnosed earlier. Potential game-changer. I’ll keep you updated.

Great post, Larry.

This is the best site for info on the trial: https://www.amylyxpsptrial.com/

Maybe add it to your text?

Thanks for that link, Kristophe. I’ve added it to the post.

Hello Dr. Golbe,

Thank you for the information and data on the AMX-0035 trial. I cannot help but share my thoughts.

The endpoint of this trial, if I understand correctly, is to slow the progression of the disease’s natural course. How is this to be assessed via the PSP-RS? An absence of a rise in the score over time or an improvement in the score? If the goal is to prevent a rise in the score over time, is there a known rate at which the PSP-RS usually rises in the absence of any intervention in order to compare this to?

I hesitate to bring this next concern up however I feel that I need to. In the absence of any known treatment for PSP, if this trial is successful then this is quite good news – anything that helps in any way is good news. However is it really? The quality of life for a patient with PSP is terrible as you (or anyone who has ever cared for or evaluated a patient or loved one with PSP) know. Therefore is extending this poor quality of life by a year truly a success? The reason I bring this up is because I would like to know if perhaps by targeting these molecular and cellular processes within the mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum, and thus reducing the stress and burden which is on these patients at the cellular level, is there any hope that perhaps there will also be some symptom improvement as a result of a lessening of burden/overload of the system and the brain’s own immune system and other processes being able to more efficiently function or discard of more abnormal proteins? And therefore some (even small) improvement in quality of life. This very well may be completely unknown. I may have asked you this in a prior post. I ask this not to be dismal or morbid but to see if there is even more hope. As you always say, hope is important.

Dear Ms. Fotouhie:

I think both of your questions are shared by many people with PSP and their families.

The answer to you first question, regarding what the patients on the study drug are compared to, is the placebo group. At the time of enrollment, each patient is randomly assigned to receive either the real study drug or an identical-appearing placebo. Of course, this plan is made quite clear in the informed consent process. Only the drug company knows the assignments. At the end of the study, the rates of progression of the PSPRS score for the two groups are compared. In this way, we don’t need to know in advance how rapidly PSP progresses. On completing their 12 months of placebo or real drug, each patient will be offered the chance to take the real drug (called the “open-label phase”).

The second question asks about the likelihood of symptomatic benefit, rather than just slowing the rate of worsening. The chance of that is low, but not zero. If the drugs do improve the function of cells affected by the PSP process, some of them may be able to recover and others (probably most) will be beyond saving. Either way, the treatment may allow cells that are still healthy to avoid becoming involved in the disease process at all, or with a major delay. What we don’t yet have is a way to restore the function of the cells already lost, though researchers are busily working on that.

Your second question implies that it may not be worthwhile merely to slow the progression of a disabling condition without curing it or improving its symptoms relative to the study baseline. My own interactions with patients in my decades of practice and my informal poll of this blog’s readers show that even a 25% slowing of progression (the benefit of AMX-0035 in ALS), which would provide one more year of life for people with PSP, would be worth the hassle and risk of side effects of a new drug. Keep in mind that in prolonging a three-year survival to a four-year survival, the drug wouldn’t prolong the most advanced, disabled stage for another year. Rather, it would prolong each of the three years by 25%.

I hope this clarifies things a bit.

Pingback: I’m glad you asked that . . . | PSP Blog

Dr. Golbe,

I really appreciate your thorough and thoughtful response. It helps to get your insight on this.