Some excellent news for you today. The orally administered drug AZP-2006 has shown early signs of slowing the progression of PSP. (Yes, you heard right!)

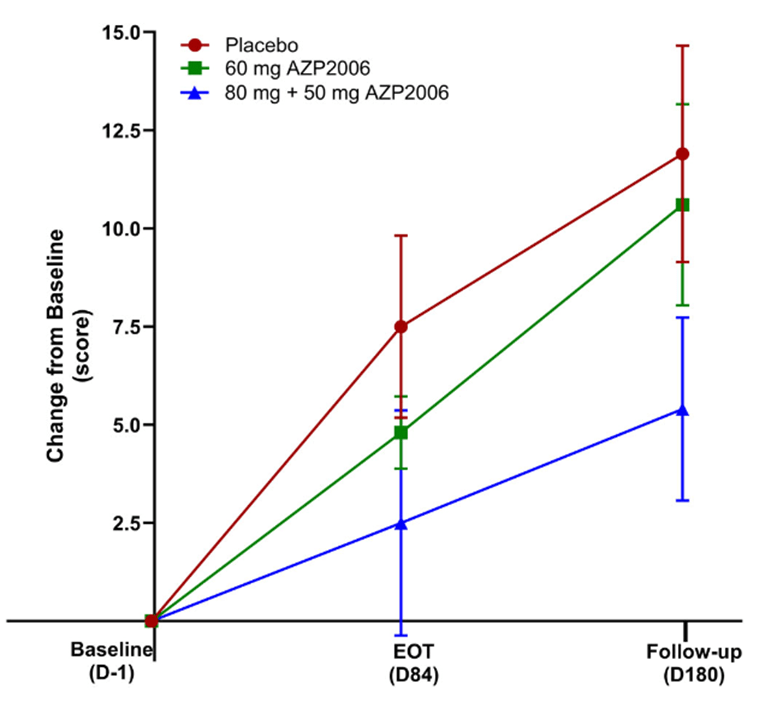

My blog post from May 9 of this year brought news that a small, open-label, Phase 1 study of AZP-2006 seemed to have slowed the progression of PSP by 31 percent. Now, the drug has completed a small, double-blind, Phase 2a trial with even better results: In the 11 patients receiving 60 mg per day, the worsening in the PSP Rating Scale score over the 3 months of the double-blind phase was a third slower than in the placebo group (identical to the result of the uncontrolled Phase 1) and in the 13 patients receiving a loading dose of 80 mg on the first day and then 50 mg per day, the apparent worsening was two-thirds slower.

It’s important for you to understand, and the authors repeatedly emphasize, that these results were not statistically significant, meaning that they could be the result of a random fluke. There were also some minor differences among the three patient groups (placebo, 60 mg, and 80 mg then 50 mg) at the study’s baseline that theoretically could have explained the results. A larger, Phase 2b study could confirm the result while having the statistical power needed to compensate for any “baseline bias” among the treatment groups.

The trial included a 3-month open-label extension. That’s where the participants on placebo for the first 3 months were offered the opportunity to convert to the active drug at 60 mg per day, while those initially on the active drug could opt to continue it. Over months 4, 5 and 6, the rate of decline of the formerly-placebo group slowed down noticeably. The other important result is that the drug showed itself to be safe and well-tolerated over the entire 6 months.

The publication’s first author is Jean-Christophe Corvol, MD, PhD, a very well-regarded, senior neurologist I know at the legendary Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière in Paris. The senior (i.e., last-named) author is Luc Defebvre, MD, PhD, at Lille University. Six of the other 16 authors are staff researchers at the sponsoring drug company, AlzProtect, of Lille, France.

In this graph, the vertical axis is the worsening in terms of the 100-point PSP Rating Scale. EOT is end of the double-blind part of the trial at Day 84. Thereafter, all participants received active AZP-2006. Note that both active-drug groups progressed more slowly than the placebo group over the first 3 months; and on active drug, the participants formerly on placebo may have slowed their progression rate. The vertical line segments represent standard deviations of the mean. (From: Corvol JC, Obadia MA, Moreau C, et al. AZP2006 in progressive supranuclear palsy: outcomes from a Phase 2a multicenter, randomized trial, and open-label extension on safety, biomarkers, and disease progression. Movement Disorders. 2025 Sep 27. doi: 10.1002/mds.70049. PMID: 41014124)

So, when will the Phase 2b study start? My May 5, 2025 post reported on the “PSP Platform Trial,” (PTP) an NIH-supported collaboration among dozens of U.S. academic centers to perform Phase 2b trials on up to three drugs simultaneously using one placebo group. One of the first three drugs, in fact, is AZP-2006. Last I knew, the PTP was expected to start late this year, but it’s now almost October and I’ve heard nothing further other than that some details remained to be ironed out with the FDA. That trial would take about 6-12 months to recruit and then another 12 months for the last patient to finish, then at least a couple of months to analyze the data.

So, how does AZP-2006 work? I’ll plagiarize my own May 9 blog post, along with its “Nerd Alert!” warning that this gets technical:

The main mechanism of action of AZP-2006 is at the lysosomes, one of the cell’s garbage disposal mechanisms, where it acts specifically at the lysosome’s prosaposin and progranulin pathways. Prosaposin is the metabolic precursor (a “parent molecule” cleaved by enzymes to produce the active molecule) of the saposins, a group of proteins required for the normal breakdown of various types of lipids that are worn out or over-produced or defective from the start. Progranulin is the precursor, as you’d guess, of granulin, which, like saposin, is involved in function of the lysosomes. But progranulin addresses disposal of proteins, not lipids. In mouse experiments, the drug also enhances the production of progranulin, mitigates the abnormal inflammatory activity in tauopathy, reduces tau aggregation, and stimulates the growth or maintenance brain cell connections.

Bottom line: This very small, Phase 2a trial was designed to show safety, not efficacy, and its slowing of PSP progression did not nearly achieve statistical significance nor exclude potential sources of random bias. But the magnitude of the (apparent) effect make this excellent news for those with PSP, present and future.