Consideration number one:

There are now ten different variants, or “phenotypes,” of PSP. The most common, PSP-Richardson syndrome, accounts for about half of those affected, and the next most common, PSP-Parkinsonism, accounts for about a third. All ten variants share the same kinds of neurofibrillary tangles, tufted astrocytes and all the other microscopic features, but their specific locations in the brain differ in emphasis. In fact, the ten have been classified into three groups: cortical PSP, subcortical PSP and PSP-RS, the last being a sort of hybrid. The differences among the ten exist only for about the first half of the disease course. After that, they all merge into what looks like PSP-RS.

What explains this (slight) diversity of anatomic predilection? We won’t know that until we know the cause of PSP, but I’ve got my theory, which I’ll tell you about after you consider this:

Consideration number two:

In 2021 I posted something about a geographical cluster of 101 people with PSP in a group of towns in northern France, which is 12 times the number expected based on surveys elsewhere. The most likely cause is the intense environmental contamination with metals dumped there by an ore processing plant. Fortunately, there have been no new cases of PSP in that area since 2016, possibly thanks to the mitigation measures taken by the local authorities starting in 2011.

In a 2015 journal publication, I did some calculations comparing the neurological features in the 92 people with PSP in the cluster at that point to those of people with “sporadic” PSP.

I found only two differences: In the cluster, the ratio of PSP-Richardson syndrome to PSP-Parkinsonism was about even, while in sporadic PSP it’s about 3:2; and the average age of symptom onset was 74.3, about a decade older than in sporadic PSP. (The area was not at all a retirement community; its age frequency structure closely resembled those of other ordinary communities in the industrialized world.) The molecular assays we performed showed no differences.

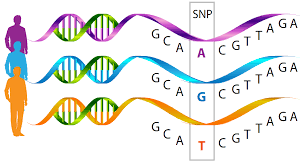

My theory:

The experts agree that the cause of most of the common neurodegenerative diseases is a genetic predisposition together with an environmental exposure. For PSP, we presently know of 14 genes, each of which has a variant in a certain percentage of the population conferring slightly elevated risk of PSP. But we don’t know how many, or what combination of those 14 are needed to set the stage for the environmental toxin. For all we know, different toxins need different numbers or combinations of PSP genetic risk factors to exert their toxicity. The only confirmed environmental risk factors for PSP are metals, but of unspecified kinds. The only other well-confirmed non-genetic PSP risk is a tendency to lesser educational attainment, which I feel is likely to act by exposing people to toxins related to manual occupations or to industrial installations or waste sites near their homes.

So, here’s how I tie all this together:

The ten PSP variants as well as the diversity of onset ages within each variant could be determined by one’s own set of PSP risk genes and by which of the possible PSP-related metals (or yet-undiscovered kinds of toxins) they encountered. The two differences between the French cluster and everyone else with PSP could be the particular types or combination of metals to which the people were exposed. That means that at its root, the cause of PSP could be an array of slightly different abnormalities at the most basic molecular level. Those differences could take the form of slightly different tau protein abnormalities across different individuals. As has already been shown, each member of the array of abnormal forms of tau (called tau “strains”) might have a predilection for a different brain area or brain cell type. That anatomic predilection would dictate the specific array of symptoms initially experienced by that individual, and that array could be different when your tau was damaged by the metals at the French site than by whatever damages tau in PSP elsewhere.

How to prove this theory:

This would take a lot of difficult research to prove, but I made a start back in 2020 with the publication of some lab experiments I suggested to a group of lab scientists at UCSF led by Dr. Aimee Kao.

She and her colleagues took stem cells from a tiny skin biopsy of a person with ordinary PSP who carried one of the known PSP risk genes. They converted the stem cells into brain cells and divided the resulting colony in two: In one half, they used the now-famous gene editing technique called CRISPR to return the variant to its normal state and left the other half with its PSP risk variant. They added chromium or nickel (the two most likely culprits at the French cluster site) to both sets of cells and found that the corrected set suffered much less damage. Furthermore, the damage involved tau aggregation and insufficient disposal of abnormal tau, just as in PSP itself.

So, now that we know 14 PSP risk genes, lab researchers could experiment with stem cells harboring different combinations thereof, along with exposure to different metals. Then, once a few such gene/metal combinations have been identified as most able to cause “PSP” in stem cells, the underlying molecular abnormalities could be worked out, drug targets identified, and drugs designed, tested, approved and prescribed.

So, you see, I’ve got it all worked out.