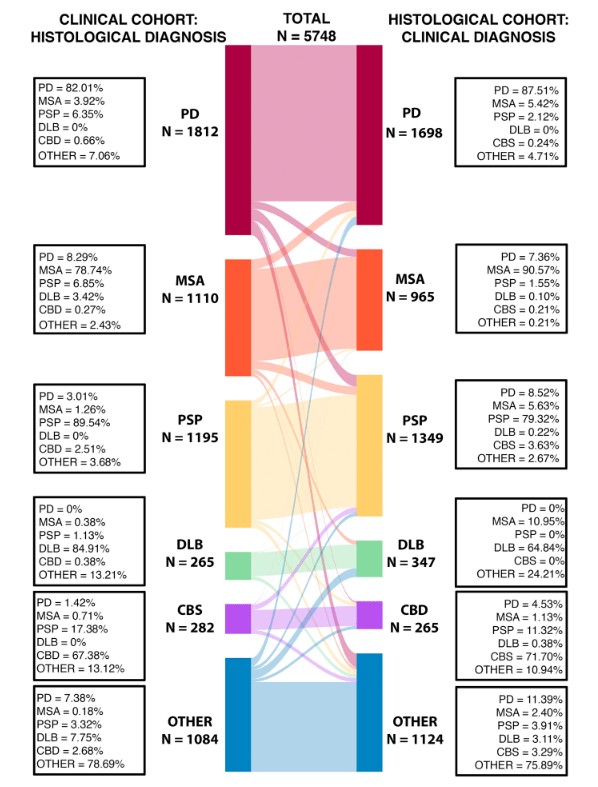

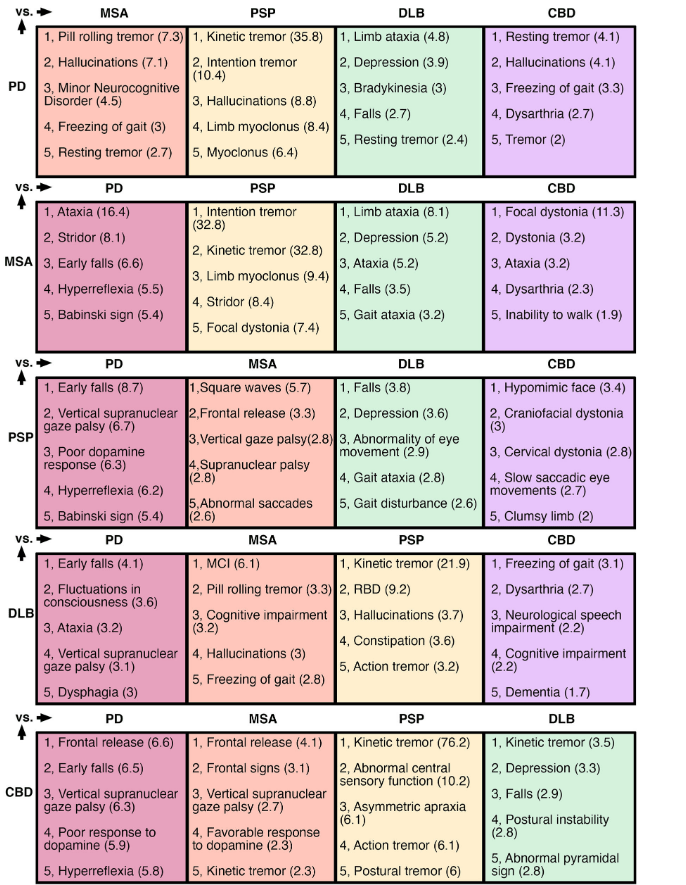

We still don’t have a great diagnostic test for PSP. The best we can do is about 80%-90% sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value. In English:

- Sensitivity is the fraction of people with PSP who give a positive result on the test.

- Specificity is the fraction of people without PSP who give a negative result on the test.

- Positive predictive value is the fraction of people with a positive test who actually have PSP.

- A single number combining these into something useful in evaluating a single individual — rather than in comparing groups — is the “area under the receiver operating curve” (AUC; see this post for an explanation). The AUC ranges from 0.50, which is no better than a coin toss, to 1.00, which is perfect accuracy. An acceptable diagnostic test typically has an AUC of at least 0.85.

Most of the studies of PSP diagnostic markers have important weaknesses such as:

- The studies frequently set up artificial situations such as distinguishing PSP only from PD or normal aging rather than from the long list of other possibilities that must be considered in the real world.

- The patients’ “true diagnoses” are usually defined by history and examination alone rather than by autopsy.

- The patients included in the study were already known to have PSP by history and exam (or sometimes by autopsy), while the purpose of the marker would be to identify PSP in its much earlier, equivocal stages or in borderline or atypical cases.

- The patients with PSP in most such studies are only those with PSP-Richardson’s syndrome, who account for only about half of all PSP in the real world.

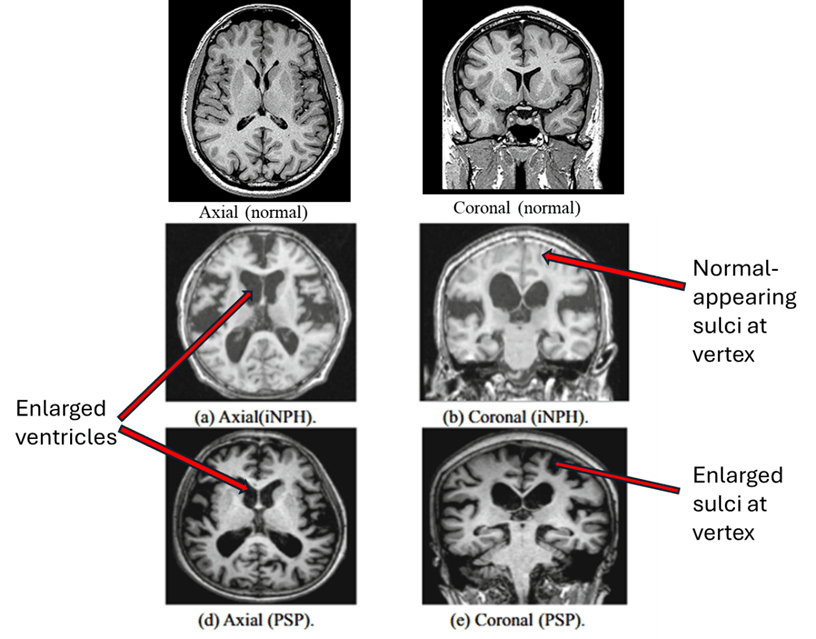

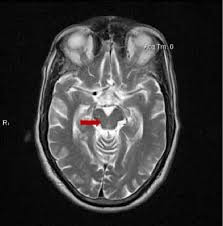

The best type of marker so far is ordinary MRI. Recently, a group of neurologists in Athens, Greece led by first author Dr. Vasilios C. Constantinides and senior author Dr. Leonidas Stefanis evaluated the specificity of various MRI-based measurements of brain atrophy. One strength of their study was that their 441 subjects included people not only with PSP and Parkinson’s disease, but also with a long list of other conditions with which PSP is sometimes confused as well as a group of healthy age-matched controls.

The single best MRI marker per this study was the area of the midbrain, the fat, V-shaped structure indicated below:

They found that MRI markers provided:

- High diagnostic value (AUC >0.950 and/or sensitivity and specificity ∼90 %) to distinguish PSP from multiple system atrophy, Parkinson’s disease, and control groups.

- Intermediate diagnostic value (AUC 0.900 to 0.950 and/or sensitivity and specificity 80 % to 90 %) to distinguish PSP from Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, and mild cognitive impairment (an early stage usually of AD).

- Insufficient diagnostic value (AUC < 0.900 or sensitivity/specificity ∼80 %) to distinguish PSP from corticobasal degeneration, normal-pressure hydrocephalus, and primary progressive aphasia (a language abnormality that can be caused by multiple specific diseases).

- Insufficient value to distinguish the non-Richardson PSP subtypes from corticobasal degeneration and primary progressive aphasia, but good performance in the other comparators.

The researchers also concluded that:

- One MRI measurement isn’t best for all the possible PSP comparators.

- Sometimes a combination of two or three measurements performed better than any single measurement.

One weakness of their method was the use of subjects diagnosed by standard history/exam (i.e., “clinical”) criteria, rather than by autopsy. Another is that their patients with PSP had had symptoms for an average of three years, so these were not subtle or early-stage cases. A letter to the journal’s editor from Dr. Bing Chen of Qingdao City, China further pointed out that the study of Constantinides and colleagues failed to account for the subtle effects of neurological medications on brain atrophy. As PSP and the comparator disorders may be treated with different sets of drugs, taking this factor into account might enhance or reduce the apparent diagnostic value of MRI atrophy measurements.

So, bottom line? Drs. Constantinides and colleagues have given us the first study of MRI markers in PSP to include meaningful numbers of subjects with non-Richardson subtypes. It’s also one of the few studies of any kind of PSP marker to include comparison of PSP a wide range of diagnostic “competitors” beyond just Parkinson’s and healthy aged persons. Another plus is that the test, routine MRI, is nearly universally available, relatively inexpensive, and non-invasive.

The hope is that Pharma companies or others with candidate drugs will now have fewer or lower hurdles in the way of initiating clinical trials.