Some not-so-good news, I’m afraid: ORION trial has been discontinued for lack of benefit.

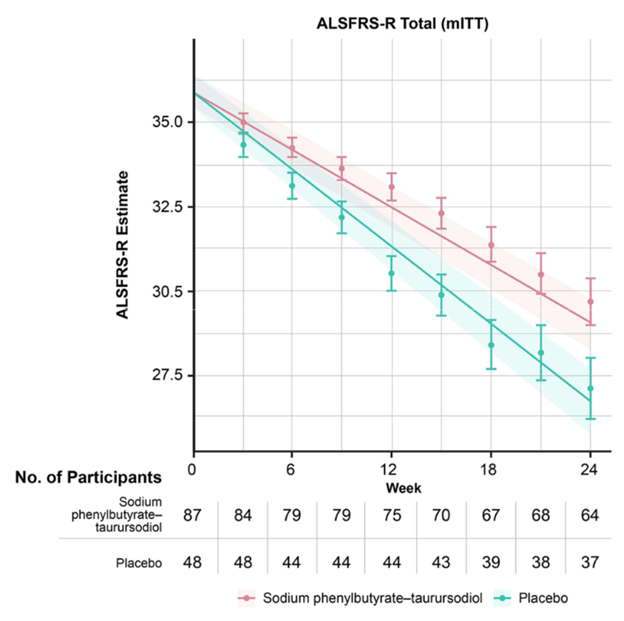

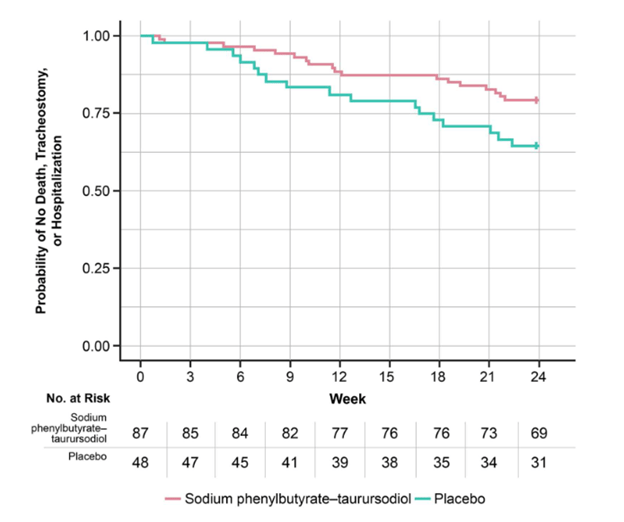

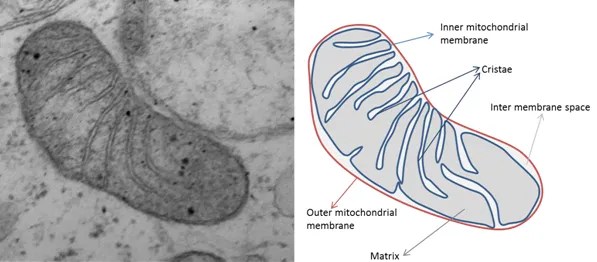

A combination of two oral drugs collectively called AMX0035 has been in a double-blind trial since late 2023. One component, sodium phenylbutyrate (brand name Buphenyl), helps brain cells get rid of misfolded, worn out or defective proteins, including tau. The other, taurursodeoxycholic acid (brain name TUDCA), stabilizes dysfunctional mitochondria. Both drugs are known to be safe in non-PSP populations, as they have long been approved and marketed for other conditions.

A few days ago, with about half of the ORION subjects having completed their 12-month double-blind observation, the sponsoring company performed an interim analysis. Their statisticians, under strict secrecy rules, “peeked” at the active drug vs. placebo assignments, comparing the groups on their degree of worsening on the PSP Rating Scale since the first visit. They found no difference, which means that allowing the remaining patients to complete their double-blind observation could never show a statistically significant improvement for the trial as a whole. Nor was there any slowing of progression on any of the secondary efficacy measures such as brain atrophy on MRI. Fortunately for the study participants, the frequency and severity of adverse effects were very low in both the active drug and placebo groups.

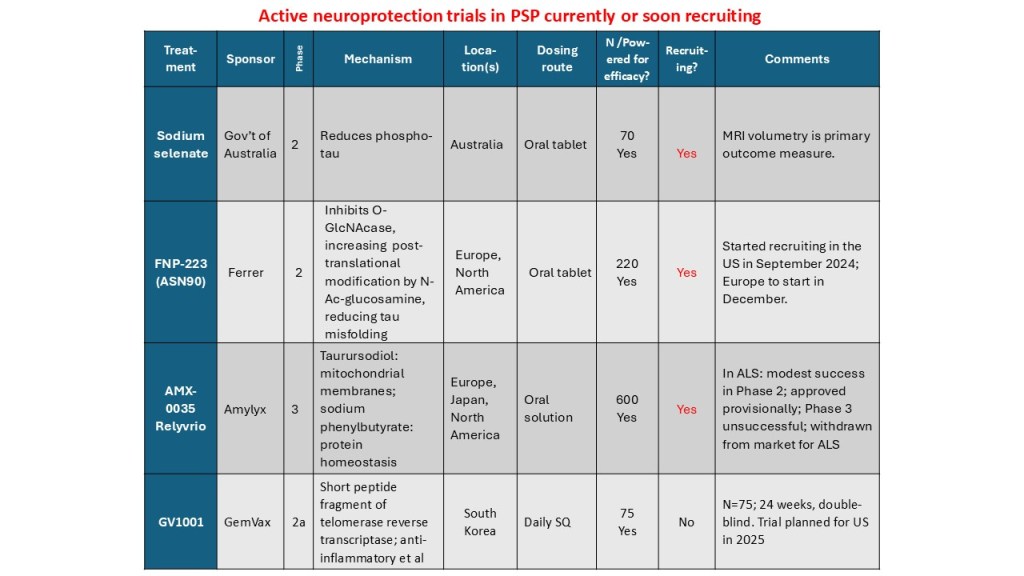

Where does PSP go from here, trial-wise? Lots of places:

- The trial of FNP-223, an oral drug that reduces abnormal phosphorylation and misfolding of tau, is nearly complete.

- A trial of NIO-752, an anti-sense oligonucleotide injected into the spinal fluid that reduces the manufacture of tau, will start in a few months.

- The PSP Platform Trial, which has teed up two two drugs and expects a third soon, should start later this year if changes in its NIH funding don’t stand in the way. Those are an active anti-tau vaccine called AADvac1 and AZP-2006, an oral drug that reduces inflammation and helps brain cells dispose of garbage. They will be tested separately, but using a common control group.

- The trial of GV-1001, a subcutaneous injection that works at the RNA level to reduce brain inflammation, will probably start in 2026 or late 2025 if all goes well.

Two drugs a bit further behind in the pipeline, based on my reading of the tea leaves, are:

- bepranemab, an anti-tau monoclonal antibody for intravenous infusion and

- an oral reverse transcriptase inhibitor called censavudine, where the results of the Phase I trial are sparsely reported to date.

That makes five new drugs to start trials within the next year or so — plus another one or two slightly later.

I liked the ORION trial’s idea to give two drugs simultaneously to address two different parts of PSP’s pathogenesis. Many PSP experts feel that at least that many drugs will be needed to do much to slow the progression of this complex disease. That’s what has proven necessary for things like AIDS, severe hypertension and many kinds of cancer. Those are only a few examples of multi-pronged attacks turning life-threatening, progressive diseases into chronic, manageable, non-disabling conditions.

I’m bullish on the same kind of thing happening to PSP.